by Takis Mastrogiannopoulos

A historical example on the occasion of the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army

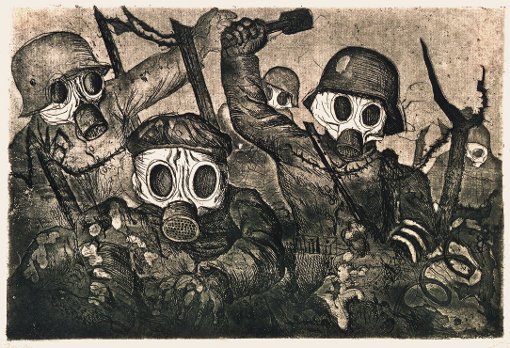

It is not the first time that the Left is faced with difficult dilemmas, such as those caused by the invasion of the Russian army in Ukraine and the war between the two countries. Dilemmas, both on a theoretical and a practical level, about what should be its position regarding the current war. I will attempt to approach the problem through a historical event which is not particularly well known.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg Empire, and his wife, in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, by a group of young Serbian romantic revolutionary nationalists, was the spark that lit the fire of the bloody First World War. The assassination of the heir to the throne was the trigger for Austria’s attack on Serbia, marking the beginning of a world war with tragic consequences for humanity, and especially for Europe.

The Habsburg Empire sent an ultimatum on July 23, 1914, and then declared war on Serbia. Rosa Luxemburg later reported that the imperial system in Austria used the assassination to attack Serbia and this was the first step that led to the generalization of the war.

“the Balkan policy of Austria was nothing more than a barefaced attempt to choke off Serbia. (…) Among Austrian imperialists the rejoicing was still greater, and they decided to use the noble corpses while they were still warm. After a hurried conference in Berlin, war was virtually decided and the ultimatum sent out as a flaming torch that was to set fire to the capitalist world at all four corners.” [1]

The “historical speech” with which Putin announced the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army attempted to do exactly the same thing: to justify an adventurist and imperialist military attack.

Anti-war reaction of the Left

How did the Serbian Left react to the declaration of war by the Habsburg Empire? The Central Committee of the Serbian Social Democratic Party met immediately and adopted an anti-war, internationalist stance. It even planned a meeting in which it called on the workers to express “the socialist position and proletarian internationalist solidarity”. But the immediate conscription declared by the government forced the party to postpone the meeting.

The Austrian troops, as part of the “punitive” campaign, attacked Serbia on July 28 and bombed Belgrade. The Serbian government and parliament were forced to move their headquarters to Nis. At the session of the Serbian parliament on July 31, the Social Democratic Party MP Dragisa Lapcevic, one of the two members of parliament for the party, in a climate of nationalist hysteria, condemned the war, which provoked an immediate reaction from the bourgeois parties and Prime Minister N. Pasic. In his speech Lapcevic was a vehement denouncer of the war:

“We don’t want this war. We do not want it for the sake of the Serbian people – for the sake of the people of Austria and Hungary – for the sake of the people of Europe and the whole world (…) Serbian social democracy calls on the government and all bourgeois parties to ensure peace for the sake of the Serbian people. In solidarity with the social democratic parties of the Balkans, it makes this appeal for the good of the Balkan peoples. As part of the Socialist International it also makes this appeal in the interests of international peace, in the interests of the proletariat, in the interests of peaceful cultural progress and development of all peoples.”

In fact, with the outbreak of war, the Serbian party, unlike most European Social-Democratic parties, voted against the military budget in the parliament as part of its anti-war policy, advocated peace without annexations and reparations and condemned the prevailing chauvinism. They were part of the initially weak anti-war European Left.

Rosa’s positions

Rosa Luxemburg welcomed the anti-war stance of the Serbian party and its deputies:

“The Serbian social democrats who protested against the war in the parliament at Belgrade and refused to vote war credits are actually traitors to the most vital interests of their own nation. In reality the Serbian socialists Laptchevic and Kaclerovic have not only enrolled their names in letters of gold in the annals of the international socialist movement, but have shown a clear historical conception of the real causes of the war. In voting against war credits they therefore have done their country the best possible service.” [2]

The advance of the Habsburg army was initially successful. It bombed and captured Belgrade. Unlike what is happening in Ukraine today, its success was temporary. The Serbian army faced the Austrian invasion victoriously. It completely defeated the invading army at the Battle of the Kolubara River, liberated Belgrade on December 14 and drove the foreign troops out of the country. This military success was also the first victory of the Entente allies against the Central Powers, but it was followed by a terrible typhus epidemic which killed 100,000 soldiers and civilians.

The question of the Austrian army’s invasion of Serbia and of the war was, of course, a matter of concern to the European Marxist Left.

Lenin

Lenin, in his article on the bankruptcy of the International, which he wrote in May and June 1915, argued that the Serbian peculiarity would not attribute a defensive, national character to the war with the Habsburg Empire, but was instead part of the general imperialist war:

“In the present war the national element is represented only by Serbia’s war against Austria. It is only in Serbia and among the Serbs that we can find a national-liberation movement of long standing, embracing millions, “the masses of the people”, a movement of which the present war of Serbia against Austria is a “continuation”. If this war were an isolated one, i.e., if it were not connected with the general European war, with the selfish and predatory aims of Britain, Russia, etc., it would have been the duty of all socialists to desire the success of the Serbian bourgeoisie as this is the only correct and absolutely inevitable conclusion to be drawn from the national element in the present war. (…) The national element in the Serbo-Austrian war is not, and cannot be, of any serious significance in the general European war.” [3]

The Bolshevik Party, at the conference of its foreign affairs section, which met in Bern, Switzerland, in February 1915, asserted that:

“The national element in the Austro-Serbian war is an entirely secondary consideration and does not affect the general imperialist character of the war” [4]

Zimmerwald

At the Zimmerwald Conference, which met in September 1915, the anti-war Left, in conditions of generalised war, condemned, despite its differences, the first great war as an imperialist war.

The position of the majority tendency, which was pacifist, crystallized in the slogan of peace. The Manifesto of the conference denounced the imperialist war:

“Irrespective of the truth as to the direct responsibility for the outbreak of the war, one thing is certain. The war which has produced this chaos is the outcome of imperialism (…) The ruling powers of capitalist society who held the fate of the nations in their hands, the monarchic as well as the republican governments, the secret diplomacy, the mighty business organizations, the bourgeois parties, the capitalist press, the Church – all these bear the full weight of responsibility for this war which arose out of the social order fostering them and protected by them, and which is being waged for their interests.” [5]

The aim of the majority of the Zimmerwald conference was to promote peace and reorganise the labour movement:

“In this unbearable situation, we, the representatives of the Socialist parties, trade unions and their minorities, we Germans, French, Italians, Russians, Poles, Letts, Rumanians, Bulgarians, Swedes, Norwegians, Dutch, and Swiss, we who stand, not on the ground of national solidarity with the exploiting class, but on the ground of the international solidarity of the proletariat and of the class struggle, have assembled to retie the torn threads of international relations and to call upon the working class to recover itself and to fight for peace. This struggle is the struggle for freedom, for the reconciliation of peoples, for Socialism” [5]

The minority of the conference, which went down in history as the “Zimmerwald Left”, although it voted for the Manifesto, put forward in its own document the view that the only answer to the imperialist war was to turn the imperialist war into a civil war:

“The prelude to this struggle is the struggle against the world war and for a quick end to the slaughter of the peoples. This struggle demands rejection [from the socialist MPs] of war credits, an exit from government ministries (…) to organize street demonstrations against the governments, propaganda for international solidarity in the trenches, demands for economic strikes, and the effort to transform such strikes, where conditions are favourable, into political struggles. The slogan is civil war, not civil peace.”[6]

Common to both trends, however, was the condemnation of the war and the participation of the socialist parties in governments of “national unity”. Both tendencies supported, despite different slogans, the socialist perspective as a response to the deadlocks of the war.

Inter-imperialist contradictions

The Russian invasion in Ukraine and the Russo-Ukrainian war, however unequal and unjust, I believe raises exactly the same questions of principle for the contemporary European Left.

This war, apart from being an unjust military invasion against an independent state, is not an isolated event, but is directly linked to the inter-imperialist contradictions in a period of deep, multi-layered crisis and unprecedented instability of the capitalist system in the post-war years. In historical terms, it has the same characteristics as Austria’s invasion of Serbia in 1914 and the Austro-Serbian war.

Zelensky’s Ukraine is today much more connected to the plans of US imperialism – as a result of the US-inspired and US-backed coup of 2014 which forcibly removed the elected president of the country, V. Yanukovych – than Serbia was a century ago, in 1914, with the Entente allies. In this respect, Zelensky’s presidency is part of the crisis, not the solution to it.

The anti-war Left in the period of the First World War was confronted with repressive measures and persecution in both the Entente and Central Powers countries. The same is happening today in Ukraine and Russia. Those who protest and condemn the war are being targeted by their governments.

In Ukraine today, the Left is being persecuted and repressed both by the government and by fascist, paramilitary forces such as the notorious Azov battalion.

The abolition of the free use of Russian and other minority languages, including Greek, the banning of the Communist Party and the decriminalisation of Nazi propaganda (!) are some of the measures that today’s unconditional supporters of Zelensky presidency are not at all bothered with.

In Russia, all anti-war demonstrations are met with violent repression by the police, with the result that thousands of demonstrators have been arrested.

It is true that the theory of imperialism as a stage of armed conflict between the major capitalist powers seemed to recede in recent decades and the notion that globalisation required stability in international relations had prevailed. However, the Russian invasion proved that the range of nuclear weapons has not ruled out the possibility of military conflicts which would, and did, directly lead to confrontation the major nuclear-armed powers.

Putin’s Russia is one side of the coin of the invasion and the war. The Biden presidency’s policy, which is a continuation of the Bush presidency’s doctrine of “war without end”, is a doctrine of imperialist action which dismembers nations, disintegrates states such as Iraq, destroys societies and destabilises the “world order”; it is the other side of the coin.

The essence of both the Russian invasion and the war in Ukraine is that the planet must once again be redivided.

Conflicts between the great powers, the United States, the powerful countries of the European Union, Russia and China, are, in the context of the crisis of the system, inevitable. Military adventures will be – and already are – on the agenda, with the risk of even a nuclear holocaust.

Once again, the left must not choose an imperialist camp. In today’s conflict it cannot support either the representative of Russian imperialism, Putin, or the long arm of American imperialism in Europe, Zelensky.

Its stance must be one of firm opposition to all kinds of military and war plans. From this point of view, the parties of the Left, in all its versions, must take the lead in building a massive national, European and world anti-war movement – a movement fighting for peace in every corner of the planet. And this struggle, like the struggle of other movements, for the protection of the environment, for democratic rights, etc., must be combined with the struggle for the social transformation of society, however outdated this position may sound nowadays.

One more small example. During the war, Lenin, in a speech to the Swiss working class youth at the “People’s House” in Zurich, in January 1917, argued, during the wave of chauvinism that embraced the European workers’ movement, that “we, the elderly, may not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution”! Lenin was then 47 years old at the time. A few months later, in October of the same year, the revolution was in full swing in the former vast tsarist empire.

History knows how to take the ruling classes by surprise, especially when they are not expecting it.

[1] Rosa Luxemburg, The Junius Pamphlet

[2] Rosa Luxemburg, The Junius Pamphlet

[3] Lenin, The Collapse of the Second International

[4] Lenin, The Conference of the R.S.D.L.P. Groups Abroad

[5] «The Zimmerwald Manifesto», in the book of Olga Hess Gankin-H.H. Fisher: The Bolsheviks and the World War. The origins of the Third International, Stanford University Press

[6] «Draft resolution of the Zimmerwald Left», in Olga Hess Gankin -H.H. Fisher, ibid