The document “The Decline of Europe and the crisis of the Left” was discussed and voted on, at the end of the 3rd conference of Internationalist Standpoint (ISp) which took place between March 30 and April 3, 2025.

Following the tradition established by ISp from its inception, we avoid rewriting the documents in order to have them updated. Our emphasis is more on the description of processes rather than a summary of events and statistics.

When updates are required on specific issues, we prefer to produce separate resolutions. This is what we did, for example, with the resolution on the impact of Trump’s election.

The initial draft of the present document was prepared in the period November and December of 2024, and that is the reason why some of the facts, figures and developments described are a few months’ old. Where an update was necessary, we did it in the form of a footnote.

The document will appear on ISp’s website in three parts. (You can read Part I here.)

European Capitalism in a Quagmire

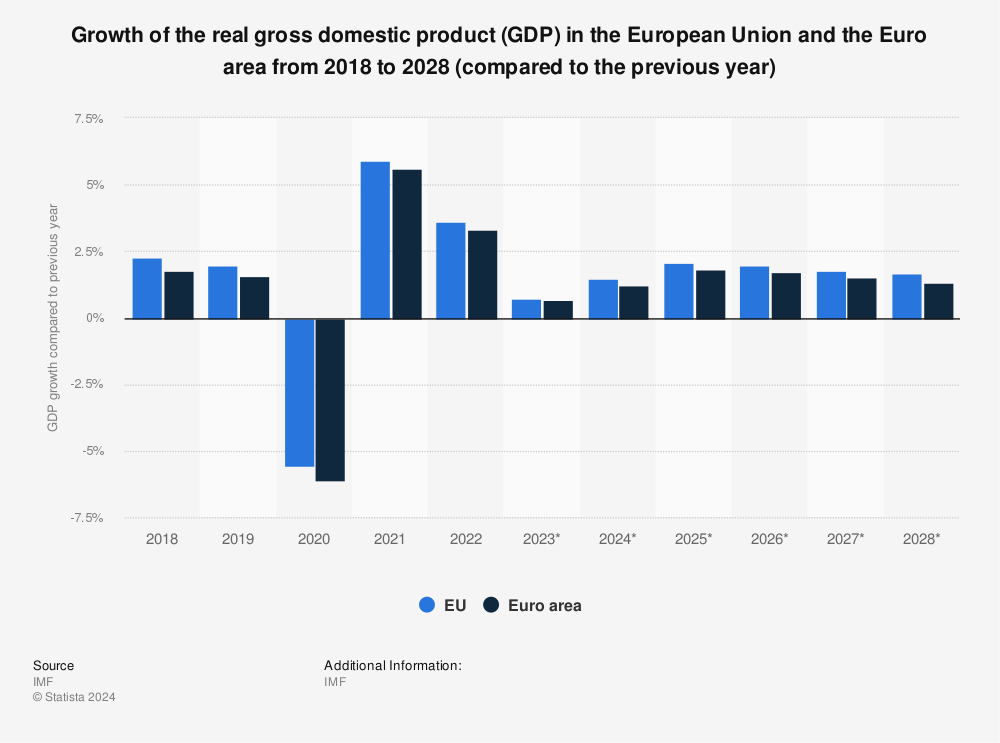

- For the whole of the 2010s growth in the main European countries has been very weak, so much so that particularly as regards the more “developed”, industrial economies of Germany, France, Britain and Italy, it can be described as stagnation. The same general picture is predicted for the next years, until the end of the decade, for the EU and for the EZ.

Find more statistics at Statista

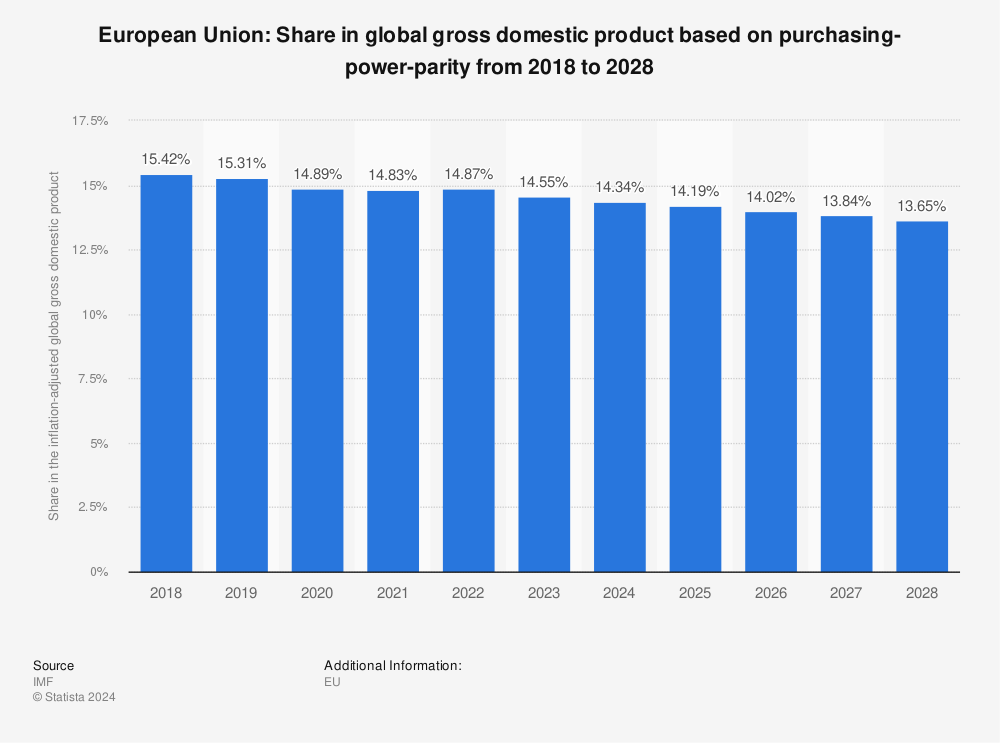

- As a result of the low rates of growth, the EU is losing ground in its share in global GDP and expected to continue doing so in the years to come. This is the reflection of the historical decline of the EU on the economic front. As if economic stagnation were not enough, Europe is entering a period of austerity (which will further undermine growth) with the re-application of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which was suspended at the time of the Covid crisis.

Find more statistics at Statista

- The SGP’s core aim is to prevent excessive deficit and debt levels, keeping budget deficits below 3% of GDP and public debt below 60% of GDP. The SGP’s fiscal constraints were suspended in 2020 to allow EU governments to prevent economic collapse at the time of the Covid pandemic, but now member states have to go back to the rules. This means fiscal tightening for countries with high debts and deficits, like Italy, France, Spain, Belgium, Greece, etc and potential tax increases (already taking place or planned in some EU countries, and also Britain). This fiscal tightening, i.e., the application of constraints on social spending and on public investments, will be taking place at a time when China and the US are following expansionary policies. This means the EU will be losing further ground in the global economy.

- The leading bourgeois circles are not attempting to hide their worries about where the EU is going. Conceptions which prevailed in EU circles, of the kind “Europe will be forged in crises” and “Europe will be able to advance on the basis of minimum consensus” are now blown to the winds, given the geopolitical antagonisms, the wars in Ukraine, Gaza and Lebanon, the economic stagnation or low growth and the divisions over migration, and “national priorities”. The notion of “greater European convergence” is today directly questioned, particularly by the far-right parties which are on the rise across the continent and Britain.

- To put it simply the 27 countries of the EU see no way forward. Greater and deeper unification as the way to overcome the crisis, proposed by several capitalist spokespersons, is empty talk. There is open talk about the “lack of vision” and the “lack of leadership”. This, of course, is not a problem with individual leaders of different European countries – it is a reflection of the generalized, multilevel crisis faced by European capitalism.

- In the past the EU used to “feed” its peoples with “visions”. The Common Market, the precedent to the EU, was supposed to help provide higher growth and standards of living and to serve peace on the Continent and internationally. Then the Economic and Monetary Union, the creation of the EU and later of the EZ was supposed to allow the European powers to lurch forward, and “become the most competitive economic block on the planet” – that was the moto that accompanied the launch of the euro at the turn of the Millennium. None of this happened.

- The “lack of vision”, is a strong characteristic of the present period the EU is passing through. In the past decades all of the policies that the European ruling classes wanted to get through, were implemented in the name of the benefits that unification was to bring about – i.e., “economic growth”, “jobs”, “prosperity”, “peace”, etc. Nothing of the sort exists today. Big sections of the ruling classes turn to nationalism and to policies that first serve their “national” interests. This of course is coupled with the rise of the Far Right.

- One of the recent blows to the idea of a “united” Europe has come from Germany itself. After forcing the European South into a nightmare on the issue of the excessive public debt after 2010, Germany encouraged rising deficits and public debts at the time of the Covid pandemic – showing their double standards. In September 2024 the German government blocked the “take-over”, i.e., the ownership of 25% of Commerzbank by the Italian UniCredit – so, following this line, the European market is “common” only if it serves the interests of the German ruling class. And a few weeks later, after the victory of the far right AfD in three consecutive federal state elections (see later), it proceeded to impose border land controls, thus dealing a blow to the Schengen Convention which allows free movement between 29 European countries [[1]]. However, the ability of the German bourgeoisie to impose its terms unilaterally, as used to be the case until the mid- 2010s, is no longer the case. Particularly so because there are serious frictions in the Franco-German axis which has always been the center of power and decision making in the EU and EZ.

Dreams of Convergence and the reality of Divergence

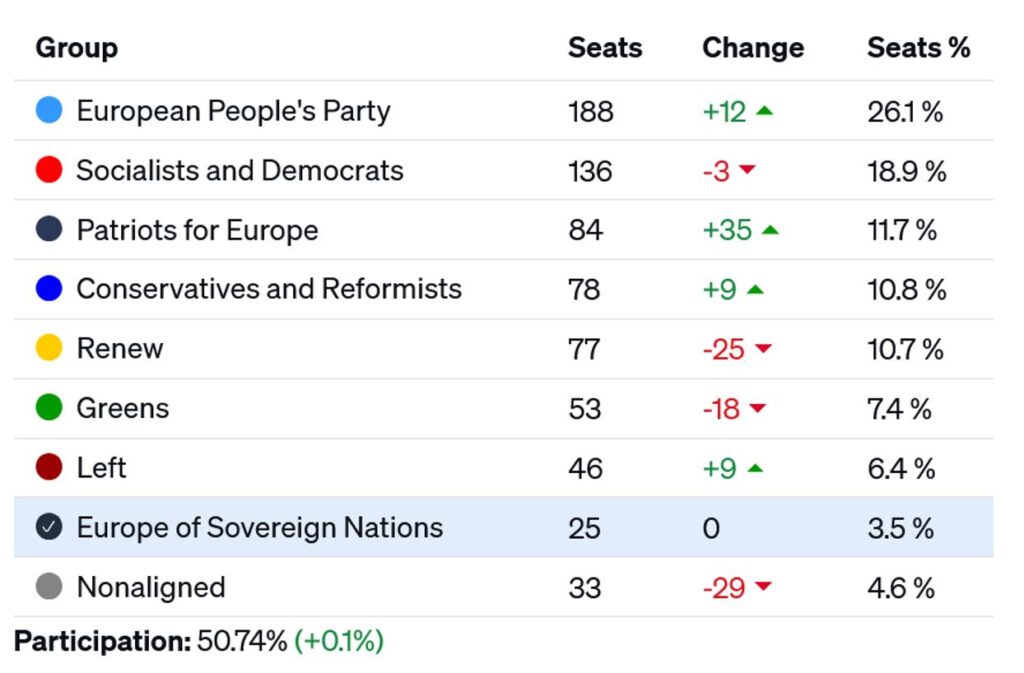

- Big sections of the European bourgeoisie call for greater convergence, as the remedy for the EU’s problems, and this is what is also reflected in the 400 pages of Draghi’s report. But these proposals come at a time when the EU is actually diverging. One expression of this is the rise of the Far Right (FR) all over Europe, which is not only pushing in the direction of more “nationalist” policies, of “less” rather than “more” Europe, but also in relation to foreign policy, particularly in relation to Russia and China. Hungary and Slovakia are opposed to the EU’s approach to the war in Ukraine, Czechia will probably join them very soon and Romania may follow.

- The supporters of “more Europe” propose majority decisions, in order to avoid the headaches caused by those member states that refuse to agree to the major EU policies that demand unanimity. This will not solve any problems. It will turn the EU more and more into a federal structure in which different states follow different policies and create different alliances. This will intensify frictions and paralysis within the EU, it will not mean “more” but “less” Europe.

- This is the direction in which the EU is moving in the present historical conjuncture. The EU has been able to achieve greater convergence at times of rapid economic growth. At times of economic recession or stagnation, paralysis ensues. Not accidentally Brexit took place in the aftermath of the 2007-8-9 economic crisis.

- These processes are a reflection of the fact that the EU is not and cannot be a unitary state, it is a formation that tries to unify as much as possible the different interests of 27 different ruling classes. In times of major contradictions, economic, social, or geopolitical, this becomes impossible, different capitalist interests tend to clash rather than converge. This process goes hand in hand with the rise of the FR across the continent.

- As a result of these contradictions, different member states provide assistance to Zelensky’s government not on behalf of the EU but of themselves. The EU is imposing tariffs on Chinese electric cars but the Chinese giant BYD is building a massive plant in Hungary to export to the rest of the EU, free of tariffs. On the issue of the European tariffs on cars, this was passed with a thin relative (not even absolute) majority in the EU, because of many countries abstaining while a number voted against, including Germany.

- The state of the European car industry is characteristic of the retreat of European manufacturing and of its inability to face the challenges of the global market and particularly to compete with Chinese products. Between the Summer and Autumn of 2024, the European auto industry was sending out signals of desperation. That refers to nearly all the major auto manufactures present in Europe. Stellantis, BMW, Mercedes Benz, Volkswagen, Porche, Volvo (now under Chinese control) Aston Martin etc, saw their shares fall in this period by 20-40 % on average, reaching 50% in the case of Stellantis. As a result, we see a reduction in the number of workers in the industry, but also open talk about closing down factories, as is the case with VW for the first time in its 87-year history, Stellantis in Italy and England etc. The European auto-industry is faced with massive over-capacity: i.e., it cannot produce as much as its capacity allows, because it cannot sell what it can produce. Capacity Utilization Rate is as low as 56% for Germany (down from 70% in 2019), 52% for Britain, 50% for France and 38% for Italy!

- The problems faced by the EU are related to the epoch of crisis faced by global capitalism and to the general economic and geopolitical instability, combined with the rise of the far-right parties which in turn is a reflection of the massive incapacity of the “left” parties to provide any perspective for the future. But it is also related to one specific factor within this context, and this is the crisis of the traditional alliance between Germany and France.

The Franco-German axis

- The two key countries in the EU and EZ are Germany and France, not only because they are the most powerful economies but also because the EU and the EZ have been based, from their inception, on the close collaboration between the two, always working together in the background, first to prepare the launch of the EU and the EZ and then to prepare the policies that they considered most appropriate for their common project. In the recent period the differences are becoming more evident and sharper; the two countries have differences over economic policy, and they both face very serious economic problems and political instability.

- In November (2024) German Chancellor Olaf Scholz sacked his Finance Minister, Kristian Lindner, of the Liberals (Free Democratic Party), thus bringing the governing tri-partite alliance of the Social-democrats (SPD), Liberals (FDA) and Greens to an abrupt end. Germany will thus go to early elections in February 2025. This is a reflection of the problems faced by the German economy and the differences within the coalition over the economic policies to be followed: the economy is facing recession or stagnation for the past two years, expected to continue through 2025; Europe has to move in the direction of cuts and austerity; there is a significant budget deficit in the region of 9 billion euros that needs to be put under check; there has been a major conflict inside the German cabinet with the Liberals demanding tax increases and cuts in government expenditure; the Social Democrats on the other hand have been pushing to “break the rules” of the Stability Pact; last but not least, the Greens have been protesting because the plans for green growth have been ditched.

- Scholz and his SPD are nearly certain to lose the coming elections. According to the recent polls only 14% of the German population say they are satisfied with the government. The Christian Democrats (with their CSU allies) are expected to receive around 32%, while SPD only 16%, and come third, after the far-right AfD. The three governing parties together could receive less than 1/3 of the vote. The parties expected to gain more from the next elections are the far right AfD (Alternative for Germany) and the left-conservative-antiimmigrant BSW (Sarah Wakenknecht Alliance).

- The state of the German economy, which until 2007 was the third largest economy on the planet (after USA and Japan) is a good indicator of the impasse faced by European capitalism. In a common statement, the top 5 economic institutes of Germany (DIW, IfW, IFo, IWH and RWI) predict that growth will be in the region of -0.1% for 2024, 0.8% for 2025 and 1.3% for 2026.

- Manufacturing was the pride of the German economy, but it’s losing ground rapidly. The case of the auto industry, failing to compete with Chinese products is a characteristic example. After Trump’s victory in the US elections, things would be much worse for Germany, and for the whole of the EU. According to Ifo, the most esteemed of the German economic institutes, German auto exports could fall by as much as 32% while the drop in pharmaceutical products could be as high as 35%.

- French economic growth is not as bad as the German one, but the picture is far away from good. Growth was at 0.7% in 2023 and is projected to be the same (0.7%) for 2024. The budget deficit is much higher than the Maastricht Treaty allows for, and the public debt is one of the highest in the EU at 110.6% in 2023, projected to 112.4% for 2024 and 113.8% for 2025. France plans around 60bnEUR in spending cuts and tax hikes next year in an attempt to cut back a widening budget deficit. The savings are required to bring the budget shortfall to 5% of economic output from around 6.1% this year. According to France’s 2025 budget, public debt is expected to rise to 115% of GDP from 113% in 2024.

- The social situation, conditioned by Macron’s neoliberal policies, has seen a rise in class struggle, (taken up later in the document) and a rise of the far-right National Rally (RN), led by Marine Le Pen. The June 2024 Euroelections marked a turning point for political developments in France, as Le Pen led the polls. Faced with this, Macron tried to keep the initiative, by immediately calling snap elections a few weeks later, in July. He tried to make use of the usual “lesser evil” blackmail, traditionally used by the centre right in France, i.e., “vote me against the extremists”. To the great disappointment of the French bourgeoisie, the main winner of the July elections was Jean Louk Melanchon, leader of the left party La France Insoumise and of the New Popular Front created to contest the elections (see later). Despite his defeat, Macron used his presidential power to form a government of his own choice, with the support of Marine Le Pen.

- In short, both Germany and France, are losing ground on the economic front, are faced with unstable and weak governments and, as will be shown later, with rising class struggles. Thus, the “brains” of the EU are preoccupied with their own internal problems and with their own “national” interests; this can only undermine the EU perspetives, particularly the ideas of greater convergence and of a bigger role by the EU in the international scene and global balance of power.

Additional features

- This document does not aim at providing a detailed picture of what is happening in different countries of Europe, on the economic, social and political level. It attempts to describe general processes. The role of the dominant economies is quite clear in determining such processes. Italy as the third major power of the EU needs to be mentioned, as well as Britain because of its economic weight though not a member of the EU. Other countries will be mentioned later on because of the importance they have in other fields, e.g., class struggle and political developments, despite not having some particular weight economically.

- Italy has been traditionally a country of great political instability within the framework of a long-standing Christian Democrat hegemony and an incapacity of the Communist Party (CP) opposition to fight for its overturn. The end of the Cold War brought the end of this historical arrangement (leading to the collapse of the traditional parties of Italy: Christian Democracy, the Italian CP and the Socialist Party) and in combination with the economic crisis and the frictions created by the processes of European integration gave rise to “unusual” political phenomena. Such phenomena have been Bossi, then Salvini and the Lega, (a federalist/independentist party from the wealthier areas, later developing into a reactionary nationalist force); Berlusconi and his Forza Italia (a liberal conservative party personally owned by a big businessman); Grillo and today Conte with the 5-star movement (a populist force, combining progressive and reactionary traits, now part of the Left in the EU parliament) and others.

- “Super Mario”, as Mario Draghi became established after stating “we’ll do whatever it takes to save the Euro” and thus supposedly saving the Euro at the time of the debt crisis of S. Europe, didn’t have much luck as PM of Italy in 2021. He only lasted 1.5 years and was forced to resign. His main “achievement” was to prepare the ground for Georgia Meloni, leader of the far-right Fratelli d’ Italia and prime minister of Italy today. Meloni has shown that, despite many “anti-systemic” declarations, once in power she adjusted very well with the needs of the Italian bourgeoisie (and the latter showed that it could accommodate a far-right representative equally well). Meloni has not challenged either the EU or NATO on any of their major political decisions since the time she took over in 2022. She now looks like the strongest leader among the major European powers, but this is because of the weakness of everybody else, not because of her own strength or the strength of the Italian economy and political system. Italy remains a weak major industrial country and this is manifested by the state of its economy: with a budget deficit of 7.4%, a public debt at 112.4% of GDP and a capacity utilization in its car industry of 38% (reflecting the more general picture of Italian manufacturing) there isn’t much room for stability.

- Britain was never able to get over the implications of the crisis of 2007-8-9. This led to Brexit, in 2016, which, of course, did not solve any one of the problems of British capitalism. It would be wrong to blame the problems of the British economy on Brexit, it is correct to state that either inside or outside the EU, there was no way out of the blind alley of British capitalism. It is an irony that the “wise” and arrogant strategists of capital on continental Europe pointed their finger to Britain, predicting doomsday because of Brexit, only to find themselves in a similar situation to that of Britain soon after that.

- The past few years have seen one of the most tumultuous political periods in recent British history: All governments between 2016 and 2024 have been weak and unstable. This was also the period when the FR was able to establish itself as a powerful player. Labour won the 2024 elections only because the Torries collapsed. Starmer is probably the most right-wing leader of the Labour party that has ever existed. Soon after his election to office he announced that he received “barren land” from the Conservatives and that a period of austerity was necessary. He has a stable parliamentary majority, due to the collapse of the Conservatives but although there has been a lull in industrial disputes since Labour’s victory, garnered by Labour being backed, at least in the short term, by key trade unions like GMB, UNISON, RMT and UNITE, this “honeymoon period”, will be short lived as groups of workers see the concessions promised peter out and austerity enacted. Potential struggles are already building amongst teachers and nurses.

- There has been a lot of talk among bourgeois analysts, in the course of 2024, that the weaker economies of the periphery i.e., the South, the East and the Balkans, are growing much faster, balancing the retreat of the main powers. This is not serious talk. The heavily indebted South, with a great dependence on tourism and agriculture cannot in anyway counterbalance the economic retreat of the major industrial economies and cannot provide a way forward.

- Two surprise political developments one in Cyprus and the second in Romania are worth mentioning. In the June 2024 Euro-elections in Cyprus, an individual who had no relationship to anyone of the political parties, Fidias Panayiotou, was elected to the European Parliament. In the first round of the presidential elections of Romania in November 2024, a candidate who was portrayed as an absolute outsider, by both mainstream and independent media (even though he was invoked by former president of Romania, Traian Băsescu, as an option for the seat of PM as early as 2011, and resurfaced in 2020 as AUR’s proposal for PM) with only around 1% in the preelection polls (he averaged 6-7% just before the elections) came first with 22.9% of the vote. Georgescu shocked the West, because of his anti-Ukraine, pro-Russian positions and will face, in the 2nd round a neo-liberal pro-Western candidate[[2]]. There is nothing progressive about these two. But they are a very powerful reminded of the huge vacuum that exists in the political scene.

- An important feature of the political situation in Europe over the last two decades has been the resurgence of what is described as “left”, “progressive” or “civic” nationalist movements in several Western European countries. In Ireland, Sinn Fein (SF) went from being the second party of nationalism in the north (Northern Ireland) to being the largest nationalist party by 2001, and then the largest party overall in 2022. In the south of Ireland, they went from a toehold with one seat in the Dail (parliament) in 1997 only to being the largest party at the general election in 2019. The Catalonian nationalist movement, with a large left component, felt confident enough to take on the Spanish state in the abortive independence referendum in 2017. The Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) overtook the Scottish Labour Party as the major party in the urban areas in the early years of this century and in 2007 became the governing party in Scotland, and came close to delivering a vote for independence in the referendum in 2014. All three movements have suffered a severe setback in the last year. SF went backwards in the local, general and European elections in the south of Ireland, SNP lost a swathe of seats to Scottish Labour in the UK General Election and left Catalonian nationalist groupings lost vote share in this year’s elections in the Spanish state. Left nationalist movements gained momentum because of, firstly, the crisis of capitalism and secondly, because of the inability of the left to answer the questions of working-class people. Just as the Left has fallen behind, now too has left nationalism, but everywhere, variants of right wing, irredentist and exclusionary nationalism have come to the fore.

- As regards the national question in general, it should be mentioned that none of the national problems characteristic of quite a number of EU countries has been resolved; on the contrary they are faced with deadlocks, with the possibility of serious conflicts reappearing. South East Mediterranea and the Balkans face the most explosive problems. The Greek-Turkish antagonism over the Aegean is becoming deeper and more dangerous, with a frenzied arms race taking place. The Cyprus problem is in complete stalemate with the Turkish side stating that it refuses to discuss anything other than two separate states on the island. The discovery of hydrocarbons in south east Mediterranea has polarized the situation even more, with Turkey blocking the efforts of Cyprus, Greece and Israel to form a block to exploit the possibilities for themselves, keeping Turkey and North Cyprus out. In the Balkans the conflict between Serbia and Albania over Kosovo remains unresolved. Serbia refuses to recognize Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence, and there are periodic flare ups particularly with the Serb-minority in northern Kosovo. The problems between North Macedonia on the one hand and Greece and Bulgaria on the other, over the issue of the name, the Bulgarian minority present there and language and historical interpretations, have stalled EU accession talks for N. Macedonia. Capitalism has no way of solving such problems. Only the working class can do so, on the basis of its common class interests. The precondition for this, of course, is the creation of mass workers’ organisations based on a Marxist perspective.

- The Eurozone crisis exposed how hollow the claims of EU economic integration and solidarity really were. And the 2015 refugee crisis made the cracks in its united policies even more clear. While most countries would not accept their proportionate share of refugees, and a few would not accept a token number of refugees, some would not even allow the desperate masses escaping war and hunger to pass through their territory on their way to Germany! Since then, the EU has made sordid deals with Turkey and Libya to limit the number of desperate people who can arrive at its borders.

- And yet, while the bourgeois press talks about “waves” of refugees “swamping” the indigenous population, almost giving the impression that there was not even any standing room left in the EU, there is a demographic crisis facing about half of the EU members, especially the most industrially developed ones. Eleven EU countries, including Germany, Italy and Spain, have fertility rates below the UN’s “ultra-low” threshold of 1.4. Even France with the highest EU fertility rate, 1.68 in 2023, is at its lowest level since the end of the war in 1945. Considering that the replacement level is said to be 2.1, the EU’s demographic outlook is bleak. Some countries will see a fall in their population in a few years. Italy, for example, could have a drop of 1 million in its population by 2030. Italy’s declining fertility rate (1.2 in 2023) and ageing population will impact its health service, retirement age and pension levels, reproductive rights, labour rights and so on.

- The falling fertility rates and aging populations will also impact the gdp growth of the EU. The EU already has a lower level of labour productivity than the US and is losing further ground. For example, between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2024, in the industrial sector, hourly labour productivity increased by 8.8% in the United States, whereas in the Eurozone it increased by just 0.8%. But bourgeois ideology never lets the facts get in the way of undermining working-class solidarity and reinforcing capitalist rule. The facts are made to stand on their head in ideological and cultural campaigns to vilify and demonise immigrants, particularly if they are Muslim and/or black.

Entering recession?

- The recent figures show that the economy of Europe as whole is in retreat and is possibly moving into recession. The figures for the Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) for November show a retreat not only as regards manufacturing but also as regards services, which until October tended to act as a counterweight to the decline in manufacturing. PMI for services in November was at 49.2 (i.e. below 50 which is the border line between growth and contraction) from 51.6 in October; while the PMI for manufacturing went further down, to 45.3 from 46 in October (i.e. manufacturing was already in contraction in October).

- The state of the European economies, the closures and the loss of full-time well-paid jobs to be replaced by badly paid or precarious employment, the attacks on trade union and democratic rights, the attack on social services, etc, has been coupled with rising inflation which has drastically eroded living standards. Despite the fact that inflation (in Europe and the US) is now close to the target of the central banks of around 2%, on average, cumulative inflation in the industrial counties (OECD average) rose 30 % between December 2019 and September 2024 but wage increases in the same period are lagging far behind. What is worse for working class people is that food inflation, (i.e. the rise in the price of food, which affects working-class living standards the most) increased by 50% over the same period. It was inevitable that these conditions would give rise to a new period of increased class struggle.

Class struggle

- 2022 and 2023 were years of heightened class struggles in a whole series of European countries, as was predictable, (see perspectives 2022 document) mainly as a result of the rising inflation and the drastic erosion of workers’ incomes. This was the opposite of what happened at the time of the Covid recession. 2024 was a year of lower levels of class struggle. The pressure on wages decreased as a result of inflation having fallen to around 2%, the struggles of the 2022-23 period had limited results and also because struggles never develop on a continuous upward path but have ups and downs. This is also linked to the role of trade union leaderships – to the fact that the struggles in their majority were forced on the Union leaderships by pressure from below. And, again, because the parties of the Left, of all colorations, have not been able to offer a fighting perspective to workers and society in general. A short reference to some of the more important struggles that were notable in Europe, follows below. Obviously, it is not possible and there is no point in listing every single struggle in each and every country.

- After the Yellow Vest (Gilets Jaunes) protests in France, which began in November 2018 and lasted throughout 2019 (with occasional flare-ups in later years), 2022 and 2023 saw a new wave of mass protests. These protests were initially sparked by rising fuel taxes and the cost of living but quickly evolved into a broader movement particularly against Macron’s attempt to increase pension age from 62 to 64. In the course of 2023, 14 general strikes were called in France. In the first strike, January 19, 2023, 2 million took part in the demonstrations nationally. 2.8 million took part in the demonstrations of January 31, according to the trade union confederation CGT. The coordination of strikes by all of France’s major trade unions –transport, energy, education, public sector, etc.– has been described as a “rare show of unity”. These protests peaked around May Day 2023, where hundreds of thousands rallied across France.

- In Germany, strikes across sectors, including transport and public services, were frequent in 2022. The key issue was rising inflation and its impact on wages, with unions such as Verdi playing a central role. Workers in the transport sector, in particular, staged walkouts, demanding better pay amidst rising living costs. Also, healthcare and postal services went on significant industrial action. German unions, particularly IG Metall, organized numerous protests, including a large May Day demonstration in 2023 that mobilized almost 300,000 people across 400 events. The country also saw climate-related protests, particularly from the youth, demanding stronger government action on environmental policies.

- The UK saw a wave of strikes, particularly in the second half of 2022. Rail workers, nurses, postal workers, and public sector employees all staged significant industrial action. Rail unions, like the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT), led multiple strikes. The “Winter of Discontent” was marked by coordinated strikes, particularly from nurses and postal workers, demanding wage increases in line with inflation. Strikes continued throughout 2023, with teachers, NHS workers, rail workers, and civil servants staging walkouts. The UK’s “summer of strikes” highlighted growing unrest across many sectors. Britain, after decades of lagging behind in struggles, in the course of 2022-23 found itself at the forefront of struggle in Europe – a development of historical, we can say, importance. The election of the Labour government led to a temporary suspension of mass action due to the government settling numerous long-standing pay disputes with the support of the tops of key trade unions.

- Spanish truck drivers, initiated protests in March 2022 against soaring fuel prices. There were also significant strikes in the healthcare and education sectors, calling for better working conditions and pay. Spanish Unions organized over 70 marches in 2023, calling for wage increases to match inflation. While many rallies focused on labor rights, there was also strong support for reducing the workweek to four days.

- Italy also saw significant labor protests over anti-poverty measures and changes introduced by Giorgia Meloni, especially among logistics, e-commerse, and food distribution workers. But in general, the Italian movement never took off in the past couple of decades after the betrayal, collapse and disintegration of the PRC (Party of Communist Refoundation – Rifondazione Comunista). Platform workers have mobilized in other countries as well – eg in Cyprus, Russia and Turkey. In Romania we had a very important strike by the teachers in secondary school education. In Belgium, 80,000 workers participated in the “National Day of Action”, called by the Unions between 20 and 22 March (2023) – the unions refused to call a strike despite the mood in the workers. In Greece, in the general lull of the working-class movement, characteristic of the situation after SYRIZA’s betrayal of 2015, two very successful general strikes took place, in November 2022 and in March 2023, indicative of the efforts of the mass movement to find its pace, despite the role played by the TU leaders. One of the most important strikes that took place in Europe was the strike against TESLA which acquired an all-Scandinavian character.

- The attack on trade union and other rights continues unabated. Meloni in Italy is making consistent efforts to limit the ability of trade unions to call strikes. In Greece, the right-wing ND (New Democracy) government with a strong presence of its far-right wing in the cabinet, has introduced the 6-day week plus legalizing the “right” of workers to work up to 13 hours a day – that makes a total of 72 hours for a working week! This blatant attack was carried through without even one shot fired by the trade unions to try to oppose it. This is one of the best ways to understand the extent of the defeat faced by the Greek working class, the responsibility for which lies of course with the leadership of SYRIZA and the renegade Tsipras.

- 2024 started with farmer mobilizations across different borders in Europe – in Germany, France, Belgium, Romania, Italy, Spain (especially Catalonia), Poland and Greece, etc organizing road blockades and rallies to raise their demands. These protests expanded from one country to another with speed, indicating that particularly in the present epoch, with fast transmission of information, protests can spread quickly and acquire mass character, without the union leaders planning or even wanting such a development. This, of course, is even more the case with workers’ struggles – the train strikes in Europe in the course of January 2023, starting from Germany and causing 80% of long-distance trains to come to a standstill, soon expanded to Italy, where we had a 24hr transport strike, to Britain (UK and North Ireland) etc. This shows the inherent and instinctive class solidarity and internationalism across borders, but the train union leaders refuse to take any initiative to organise/coordinate struggle on an all-European basis. As a result, we see moves by workers in various countries to move to what is described as “independent unions”, “grass roots Unions”, “base committees”, reflecting different traditions from country to country. These are important moves, particularly by new layers of workers outside the traditional industries, but they are still at an incipient stage.

- We are in a period of rising class struggle. Not only in Europe but globally. This will inevitably continue throughout the period we are going through because the capitalist system has no way of overcoming its crisis and providing better conditions of life for the working class, the youth and the poor. The exceptional characteristic of the present period however is that the “radicalism” developing in society is not directed towards the left but towards the right, leading to the re-emergence on a mass scale of the Far Right, to an extent we have never seen since WWII. The reasons are obviously related to the crisis of the Left – in an epoch of economic and social crisis reformists are not in a position to offer reforms, so they end up in an existential crisis which in turn bears its cost on the working class.

The Far Right

- The emergence of the Far Right and its development into a major force in Europe and internationally has been extensively taken up in the document “The Rise of the Far Right and the battle against it” of the last conference of ISp (March 24). In the present document we’ll deal with some updates and repeat some of the general conclusions.

- The most recent elections to the time the present document is being drafted, have been the ones in Austria (30.09.2024). The winner was the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) with 28.8% and an increase of 12.6 percentage points (pp) since the previous elections in 2019. The traditional right-wing People’s Party, ÖVP, lost 11.1 pp down to 26.3%; the Social-democrats, SPÖ, received 21.1%, marginally lower than 2019; and the Greens, paid their presence in the previous government, losing 5.6 pp down to 8,3%.

- In the weeks before the Austrian elections we had elections in three federal states in Germany. In Brandenburg (22.09.2024) the far right AfD came second, with 29.2% (up by 5.7 pp from the 2019 elections) only marginally behind the Social-democratic SPD which ended first with 30.9%. The Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) debuted at 13.5%; the Greens collapsed and fell short of the 5% threshold, losing all their seats. The Left (Die Linke) collapsed to 3% (also missing the 5% threshold), from 10.7% in 2019. A similar pattern was repeated in Saxony and Thuringia on September 1st. In Saxony the AfD won 30.6%, marginally behind the Christian Democrats (CDU) which received 31.9% and BSW debuted at 11.8%. In Thuringia the AfD came first with 32.8% far above the second, CDU, which won 23.6%; BSW received 15.8% while Die Linke (which was leading the state government together with the SPD and Greens) collapsed to 13% from 31%.

- The pattern is similar all over Europe: the traditional bourgeois parties, Conservative (Christian Democrat) and Social Democratic, are losing ground; the winner is the Far Right; the Left parties fail to provide any kind of perspective and are facing defeats and, often, marginalization and crisis.

- In November 2023, in the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ far-right Freedom Party (PVV) won the Dutch general elections. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni was elected as Prime Minister following the general elections held on September 25, 2022. In Hungary Victor Orbán has been continuously in power, since his 2010 re-election, having won multiple consecutive terms, including his most recent re-election in April 2022.

- In France Marine Le Pen has been steadily increasing her appeal over the past decade: In the 2012 Presidential Election (her first run for president) she finished third in the first round with 17.9% of the vote. In the 2017 Presidential Election she reached the second round but lost to Emmanuel Macron with 33.9% of the vote (Macron got 66.1%). In the 2022 (April) presidential elections she reached the second round but lost to again to Macron, receiving 41.5% of vote, Macron winning with 58.5%. In Poland the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) has been in government since 2015.

- Similar processes exist in Scandinavia. In Finland, as of 2023, the Finns Party (formerly True Finns) is in a coalition government. In Sweden the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna, SD) became the second-largest party, in the 2022 general election, securing 20.5%. In Norway the Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet, FrP) received 11.7% in the 2021 parliamentary elections. Poland is also run for most of the past 20 years by the Law and Justice Party (PiS) and in Belgium, the two far-right parties, New Flemish Alliance and Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest) received around 28% of the total vote and 50% of the Flemish vote.

- The reality of Southern Europe is a clear testimony of the relation between the crisis of the Left and the rise of the FR. Italy is an example: the second Prodi government marked, on the one hand, the definitive shift of the “progressive” (so called) pole into a liberal framework and on the other hand, the exclusion of leftist forces from parliamentary representation and the disintegration of the PRC. This created the conditions for the rise of an “ambiguous” movement like the Five Star Movement, which, by the end of the following decade, consolidated reactionary support in the country through its government with the League. In the rest of the countries of southern Europe we see similar, though not identical processes. The rise of the FR takes part in the second part of the 2010s, i.e. after the masses turned to the parties of the New Left (in Cyprus they elected the traditional left party, AKEL, to power for the first time in its history) in the aftermath of the 2007-8-9 crisis, only to be massively disappointed. The FR, taking advantage of the economic and social problems as well as the crisis of the Left, experienced very fast growth. In Greece, the far-right parties in the 2024 EU elections received between them an unprecedented 21% of the vote – combined with an equally unprecedented abstention rate of nearly 60%. In Portugal the far-right Chega received 1.3% in 2019, 7.2% (12 seats) in the 2022 and 18.1% (50 seats) in the 2024 elections. In Cyprus, ELAM, sister organisation of the Greek Golden Dawn with clear neofascist elements in its programme and activities, received only 0.2% in the EU elections of 2009; in 2014, 2.7%; in 2019, 8.3% and in 2024, 11.2%, becoming the third major political force on the island. In Spain, VOX, launched in 2014, won 10.3% (24 deputies) in the April 2019 general elections and 15.1% (52 seats) in the November elections of the same year. In the 2023 general elections it lost some ground but still received 12.4% of the vote and remained third force.

- What needs to be repeated here as well, already stressed in previous material by ISp is that the FR parties are not fascist parties. The fundamental dividing line is that fascism destroys physically the organisations of the working class and the basic bourgeois rights provided in a parliamentary system. The far-right parties of the present epoch cannot do that, the balance of power does not allow them. However, the damage they can incur, by suppressing democratic, trade union, women’s, lgbtq+ rights, cannot be underestimated. Despite this, there is time for the working class to regroup its forces and fight back.

The third part will be posted on Tuesday April 22

[1] This was not the first time the Schengen system faced blows. Since the “refugee crisis” of 2015 and then at the time of the Covid pandemic, many countries introduced border controls and kept them for years. It is clear that even on this level there are no safeguards against blatantly ignoring the rules, and no legal avenues to pursue in such situations.

[2] In the end, Georgescu was prohibited from running in the new round of elections “for breach of the constitution” and is currently placed under judicial control. According to the Romanian authorities, they found evidence of “unfair campaign practices” and of armed groups that were prepared to destabilize the state on behalf of Georgescu.