After weeks of negotiation, a new Irish government was formed in February 2025 by the two traditional capitalist parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael. As they fell short of the total number of TDs (Teachta Dála-or members of parliament) required to form a majority government after the November 2024 election they will be propped up by eight Regional Independents. The Regional independents are a loose coalition of TDs, mostly from rural areas, all of whom stand on the right of politics, and most of whom were associated with one or other of the large parties in the past.

[See links for further analysis both before and after the election]

Fine Gael and Fianna Fail together won 43% of the vote in the election, an historic low for the combined support for the two parties. This result, and their dependence on the support of maverick TDs with unpredictable positions on some issues, means that the government is relatively weak and might not see through its full five-year term. As ever in politics however, events will determine whether this is the case, and the turmoil unleashed by the second Trump term may cause severe damage the Irish economic model and mass upheavals in the months and years to come.

Sinn Fein, the largest opposition party before the election, lost momentum and is engaged in a process of reevaluating its tactics and strategy. It is simultaneously talking up the idea of a future left government, built around a possible alliance with the Labour Party, the Social Democrats and the Green Party, and is moving right on immigration, neutrality and other issues.

[See links for previous analysis of Sinn Fein’s difficulties before the election and prospects after]

The left, including the Trotskyist or ex-Trotskyist left, also went backwards in the election, losing three of its existing five seats (though it could be argued that it also gained one with the election of Seamus Healy in Tipperary-see below). Left activists across Europe and globally have been inspired by the electoral success of the Irish far left in recent decades. This success began with one council seat in 1991 and has been sustained over 35 years with peaks and troughs. It is a notable collective achievement but the relative loss of momentum for the far left in the local and general elections in 2024 requires careful analysis, as do its successes and failures over nearly four decades.

It is important that the left’s intervention into electoral politics is understood in its full context-a context that includes the historic weakness of both social democratic and Stalinist currents in Ireland, and an electoral system which is favourable to small parties and independent candidates. A key question is whether there is something exceptional in the Irish situation which means the success of Trotskyist or Trotskyist-derived groups cannot be easily replicated elsewhere or are there generalisable lessons which can be applied widely.

There is a long history in Irish politics of independent candidates winning seats in almost every constituency. The electoral system allows for this as each constituency has three, four or five seats, and it is possible to win a Dail (parliament) seat with 10 to 15% of the first preference vote, so long as transfers then begin to accrue as the surplus votes of other candidates are redistributed. Since the late 1970s the relatively favourable system has assisted a modest number of left candidates to win seats to the Dail. Sometimes this is for one term only, but often success leads to further success and strong candidates retain their seats through successive elections.

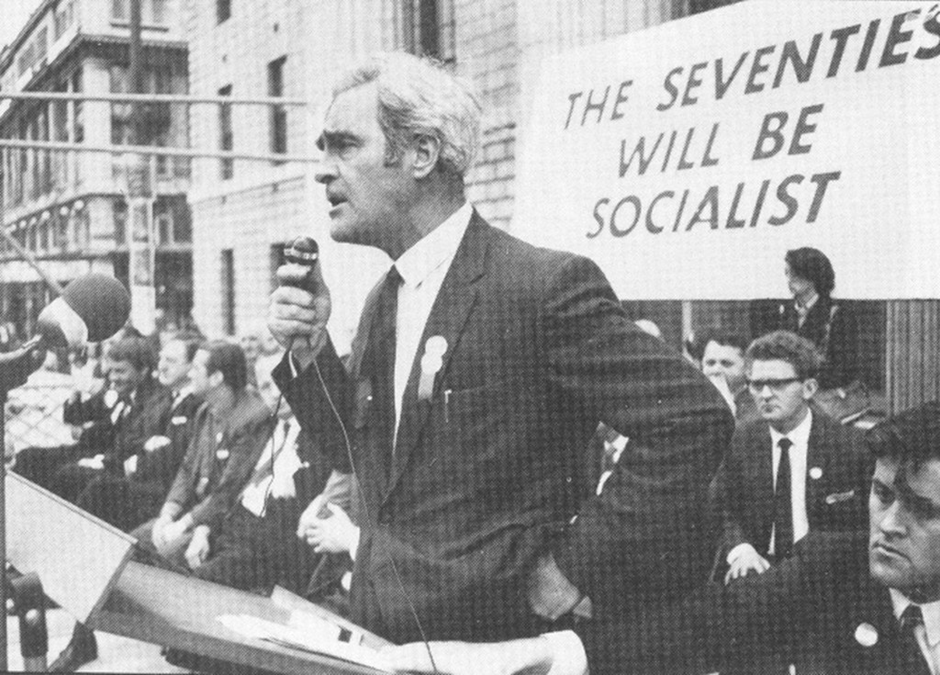

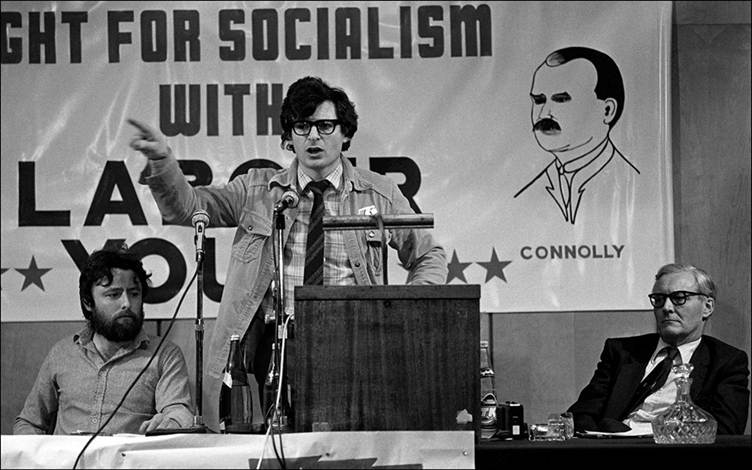

“The Seventies Will Be Socialist”

The success of the left has been assisted by the failures of the Irish Labour Party. Ireland is noteworthy for never having a social-democratic-led government, or a social democratic (or Stalinist) party with a mass base. When the Labour Party has moved to the left, and threatened to gain mass support, it has always quickly reverted to type, moved right, and shed votes.

In 1969 the then Labour Party leader, Brendan Corish, declared that “the 70s will be socialist”, and in that year’s election the Labour Party gained an historic high of 19.3% of the vote. Since the foundation of the Irish state in 1921 Labour had tended to attract 10% of the vote on average and so this represented a doubling of its support and opened up the possibility of further growth in the 1970s. It was in this period that comrades who were affiliated to the Committee for a Workers International (CWI) worked within the Labour Party, organising around the Militant newspaper, and sought to push it to the left.

Expectations were raised and then dashed as the Labour leadership moved to the right and into coalition with the pro-capitalist Fine Gael party. In 1976 many left activists split away to form the Socialist Labor Party (SLP). Militant stayed in the Labour Party, but other left groupings joined the SLP, which allowed factions and tendencies (there was a faction associated with the Socialist Workers Movement-affiliated to the International Socialist Tendency, for example).

In the 1979 general election, the most prominent member of the SLP, Noel Browne, won a Dail seat. Browne was a doctor and psychiatrist who had been a prominent member of a coalition government after the Second World War, when he introduced life-saving programs to combat tuberculosis and engaged in conflict with the then all-powerful Catholic Bishops over a proposed scheme to support mothers and babies.

His success in 1979 was in contrast to the low votes achieved by other SLP candidates in the election, and was a harbinger of what was to become common over following decades: strong candidates with a good local base and who had engaged in hard work on the ground, or who had a high media profile, could win left seats in individual constituencies, but there was a tendency for this not to generalise and become a national phenomenon. Such a breakthrough moment has eluded the left, with the partial exception of The Workers Party in 1989, and the high point achieved by People Before Profit-Solidarity in the period 2014-2016 (when it held 28 council seats and six seats in the Dail).

The Growth of the Workers Party

The SLP dissolved in 1980. Around this time the Workers Party (WP) began to slowly but steadily grow. The WP emerged from the “Official” wing of Sinn Fein and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) after the 1969 split in the Republican Movement. The Officials were moving left, under the influence of Communist Party figures, and were fiercely opposed to the “Provisional” wing of the Movement, which is direct ancestor of today’s Sinn Fein party.

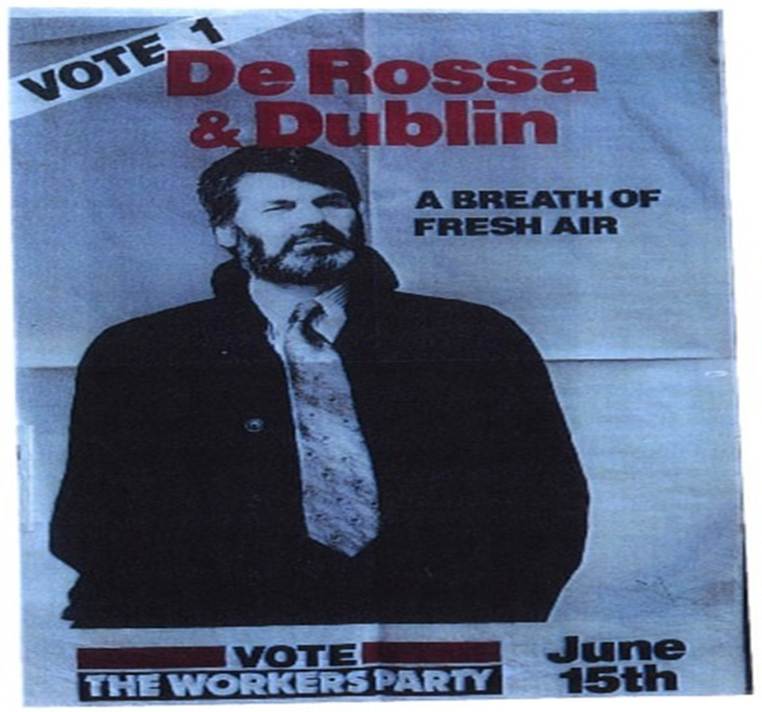

The Workers Party were and are a pro-Stalinist group and supported the Soviet Union and the Stalinist regimes of Eastern Europe, China, North Korea and elsewhere. In the workers movement they tended to take conservative positions, on industrial disputes for example. They focused on local constituency work and in the 1981 election broke through and had their first TD elected, Joe Sherlock in Cork. In the next two elections, they won three and two seats respectfully, and then in 1987 four. In 1989 the WP made a major breakthrough when they won seven seats, mostly centred in Dublin, plus a European seat in elections held on the same day and overtook the Labour Party in urban working-class areas. It won 5% of the vote nationally.

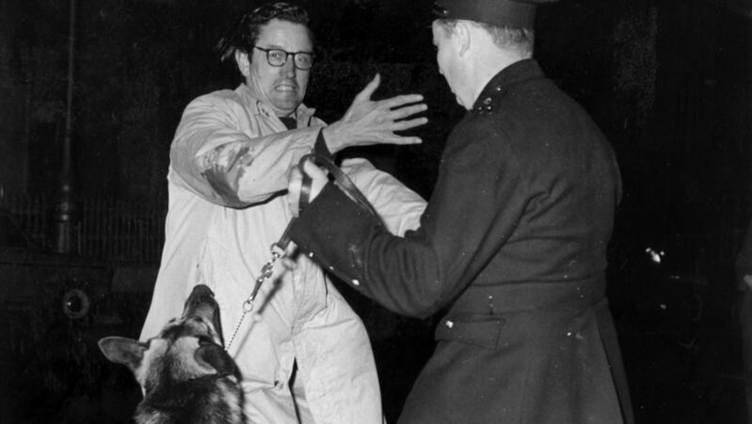

Workers Party cadres felt confident that the 1990s would be their decade, and they could continue to progress through electoral politics. This, however, was not to be the case. Not long after their successes in the 1989 elections political upheavals in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe brought an end to the Stalinist regimes. This challenged the world view of the Workers Party, and similar parties across Europe. Within months, a dispute had erupted within the Workers Party between a wing which clearly stated its wish to move in a social democratic direction, and another which was in favour of continuing with its formal adherence to Marxist-Leninism. The dispute crystallized around the alleged existence of an armed wing of the party -the Official IRA- and its continuing use for fundraising through robbery and expropriation, and for control of communities in Catholic working-class areas in the north.

The Marxist wing denied that the Official IRA still existed, and the social democratic wing walked out to form a new party, Democratic Left. Six of the seven TDs went with Democratic Left, a grouping which first formed an electoral alliance with the Labour Party and then folded into it. The Workers Party were left with one TD only, long-time leader, Thomas McGiolla. He lost his seat at the next election, and the Workers Party have struggled ever since to re-establish an electoral base. Currently it has one councillor only in all of Ireland- Ted Tynan in Cork.

The Workers’ Party were and are very different from parties of the Trotskyist far left, but from the perspective of electoral politics, their vote was very much from the working class and was cast consciously for a party which stood on the left of Irish politics. It seemed to represent a clear class-based alternative at the time, and its relative success in gaining seven seats in parliament, one MEP seat, and a national profile has never been replicated by any far-left party.

Left Independents Win Dail Seats

The Workers Party generalised success was accompanied by local successes for the left crystallised around prominent and charismatic individuals. Jim Kemmy won a Dail seat in Limerick in 1981, standing for the Democratic Socialist Party. Like the Workers Party, Kemmy was fiercely anti-nationalist and anti-Provisional IRA. He took a strong stance on social issues and opened a family planning clinic in Limerick in 1975, much against the prevailing tide. For this, he was attacked by the Catholic church hierarchy, and he lost his seat in the second of two general elections in 1982. He managed to come back and win again in 1987 and 1989. Like the Democratic Left TDs he eventually joined the Labour Party, where he did not stand out as being on the left of the Party. He died at a relatively young age in the early 1990s.

The 1980s also saw the election of independent left Tony Gregory to the Dail from the Dublin Central constituency. Gregory had been a member successively of Official Sinn Fein, the Irish Republican Socialist Party (a break away from the Officials, whose armed wing the Irish National Liberation Army carried out a series of vicious sectarian attacks in Northern Ireland) and then the Socialist Labor Party. He was always an independent-minded individual however and won a seat in the 1982 election as an Independent. He immediately entered an arrangement to prop up the Fianna Fail government, led by the notoriously corrupt Charles Haughey in the so-called “Gregory Deal”. In return for his support, he extracted a series of promises for his constituency. He was rightly criticised for this by the left, but he never accepted that he had made a mistake. He continued to remain resolutely focused on his working-class constituents, with no obvious wider agenda. When he died in 2009, he was succeeded by his election agent Maureen O’Sullivan who held the seat until her retirement in 2020.

In the 1980s the Workers and Unemployed Action Group (WUAG) began to develop a base in Tipperary, winning a number of council seats from 1985 onwards. In the year 2000 it succeeded in winning a Dail seat with Seamus Healy as candidate. This group, resolutely localist, did not have distinctively far left positions, but has a distant connection with Trotskyism: Healy’s brother Paddy, the main organizer of the WUAG, was one of the leaders of a small Irish “Lambertist” group in the early 1970s (the League for a Workers Republic). Healy has won and lost seats across several elections, and in 2024 once again returned to the Dail.

The Sligo-Leitrim Independent Socialist Organisation (ISO) was established by Declan Bree and others in 1974 in a largely rural constituency running along the border with Northern Ireland. Bree was active in the youth wing of the Communist Party of Ireland (the Connolly Youth Movement) in the late 1960s and early 1970s and became its National Chairperson. He was an elected councillor from 1974 and built up his voting base to a high point of 13% in 1989 when he narrowly missed out on a Dail seat. The ISO merged with Labour in 1991, and Bree was elected to the Dail as a Labour candidate in 1992.

Militant Expelled and “The Spring Tide”

The seismic shift in geopolitics and economics caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European USSR-aligned states pulled away the underpinnings for the Workers Party and correspondingly strengthened the Labour Party which now had no coherent, nationwide threat to its left. It took keen advantage, formed an alliance with Democratic Left (DL) and then subsumed the majority of its TDs. It was further strengthened when it absorbed Jim Kemmy’s Democratic Socialist Party and Declan Brees Sligo-Leitrim Independent Socialist Organization.

The so-called “Spring Tide” in the 1992 general election (Dick Spring was leader of the party at the time) saw Labour win 19.5% of the vote, alongside Democratic Left, and it returned its highest number ever of TDs. Rather than remaining independent of the main capitalist parties it predictably entered coalition, firstly with Fianna Fail (1992-1994) and then with Fianna Fail and the DL (1994-1997). It imposed right wing policies and as a result, its vote was halved at the next general election in 1997.

It was during this period that the Socialist Party began its journey in electoral politics. Militant had organised within the Labour Party from the early 1970s to 1989. It sought to build a strong left wing and to commit Labour to socialist policies. The Socialist Party emerged after the expulsion of Militant from the Labour Party in 1989. In 1991 Joe Higgins, who had previously been selected as a Dail candidate by the Labour Party before his expulsion, stood as a local election candidate in Mulhuddart, on the western outskirts of Dublin. He was elected to the council and since 1991 there has been a continuous presence for far left or Trotskyist representatives in Ireland, at council, Dail or European Parliament level. Since 1997 there has been unbroken representation in the Dail, except for one five-year period between 2007 and 2011 when Joe Higgins lost his seat.

For many years the Socialist Party approach was patient, focused, and tactically adept. Candidates in urban working-class areas worked hard on the ground, and at a national level. The Party sought to intervene into or to build and create working class movements around issues such as water charges and bin charges. It was successful in many ways and increasingly gained national prominence. Joe Higgins was a nationally known representative and seen by everyone as being on the left and a fighter. In time, he was joined in the Dail by Clare Daly, Ruth Coppinger, Mick Barry and Paul Murphy, all first elected from the SP, and Joan Collins, elected after she left the SP. Several other far left TDs were elected from People Before Profit.

The far left was a factor in national politics from the 1990s onwards, sometimes a significant factor. Whilst there was electoral success however, it was limited. Strong candidates with a good local base and who engaged in hard work in campaigns and struggles held their own but there was to be no national breakthrough. The factors which lead to the far left losing momentum and then falling back are explored and analysed in Part Two (which will be published in the coming days).