Document approved at the National Assembly of ControVento, Bologna October 19, 2024. “Contro Vento”, meaning “against the wind”, is an Italian revolutionary Marxist organisation, in close collaboration with Internationalist Standpoint.

_______________________

The need to close ranks against the tide by emphasizing working-class independence and fostering a united front, amidst labor disorganization and the reactionary right-wing government

More than two years after the founding of ControVento, it is useful to take stock of our experience to better understand the current situation and outline the path to continue our journey.

1- When we were born in 2022, we found ourselves on two fundamental axes as emerged from the Founding Statement:

- Our configuration as a political laboratory: that is, our construction as a plural and transitional gathering place to collectively redefine a political and organizational proposal, by interacting with conflicts in production relations and international movements. ControVento in this season thus included comrades with different analyses, positions, and political placements within the programmatic perimeter of the Founding Statement without arriving at a synthesis or a majority choice. We did not structure ourselves as a complete organization with a consequent democratic centralism but carried out a temporary path of political reorganization.

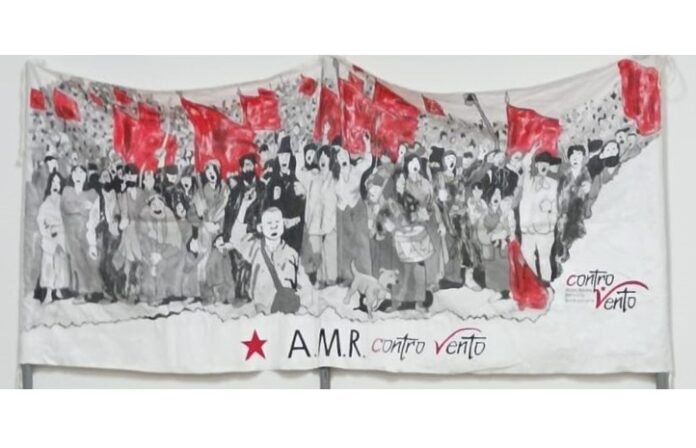

- A revolutionary communist programmatic framework. The collective redefinition of a political project is based, in any case, on the experience of revolutionary Marxism of the twentieth century, aware of its programmatic assertions and methodological practices but also of the sectarian or movementist drifts that characterized it. The AMR ControVento, that is, was founded on a programmatic framework centered on six founding points: opposition to the ruling classes and their governments, the perspective of a government of workers, the connection between demands and an anti-capitalist perspective, a dialectical relationship between vanguard and self-organization, a councilist practice, and an international outlook.

2- This choice was the result of various considerations:

- The rationalization of a transition phase in Italy, triggered by the Great Crisis of 2006/09 and the fragmentation of the left after the second Prodi government [PRC and surroundings], marked by particular disorganization and division of the working class [where the cycles of struggle between sectors break down, identities fragment, and mass movements centered on work exhaust]; an isolation of the vanguard from mass dynamics; the penetration of reactionary movements into the subordinate classes and even organized labor (Grillo, Salvini, and then Meloni); the shrinking of the left’s people [the widespread political consciousness in Italy that related the opposition between subordinate and dominant classes, the capital/labor contradiction, and the perspective of social transformation].

- The limits of the strategy of building the party and the revolutionary process of the PCL and, more generally, in the revolutionary left: in this transition, it emerged that something was not working in our political action, with its focus on the direction of struggles and movements [propaganda, participation, and demarcation], in the belief that tensions accumulate and thus sooner or later ignite. Even the reformist and centrist sectors lose organization and mass projection while mass conflicts lose boundaries and class identity. The political situation is therefore characterized less by the historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat [Transitional Program, 1938], not only by the marginality of revolutionary parties (evident), but even by a historical crisis of the very organization of the proletariat.

- The opening of a reflection on party and class to counteract the vanguardist drifts (substitutism to mass dynamics) and sectarian ones (verticalism and international-party). The organization on a vanguard program is essential for a transition project, because anti-capitalism in production relations and social conflicts does not in itself generate the socialization of the means of production. But in revolutionary politics it is equally essential to develop a mass propensity and a councilist perspective (the conquest of the whole class and its self-organization), in a free and equal confrontation among different positions, even organized in the party, developing a democratic centralism that guarantees internal dialectics [see Working-class, Party and Councils].

- The extreme weakness and dispersion of our forces: ControVento was born by reweaving a relationship between a small nucleus of comrades who left the PCL over the years, worn out by its progressive vanguardist and verticalist drift; a few dozen militants and activists scattered across different territories, engaged on various union and social fronts, struggled to share daily practices and interventions in an even more fragmented class initiative. The choice to start a process of collective re-elaboration then seemed the most suitable for the conditions of reality, trying to understand the dynamics of this new season and regroup new forces through a process of analysis of the composition and dynamics of class struggle with a gradual re-elaboration of practices and strategies.

3- In the difficulty of the times, we counted on a progressive reactivation of social conflicts, on partial recompositions of class subjectivities in struggles, and on political review in sectors of the vanguard capable of marking continuity solutions and thus opening possible new paths. We hoped that the end of the pandemic emergence and its further ideological divisions in the left and movements (vaccinations and health management), along with the worsening of certain elements of the economic crisis and the growing role of reactionary rights, could open a new season of mobilization on one side and paths of re-elaboration and re-articulation in the left. In this perspective, the PCL and other major organizations of the Trotskyist tradition (SA and SCR) seemed to play a role not only self-centered but above all of pathological re-proposition of out-of-season paths:

- The PCL (Workers’Comunist Party) with a paroxysmal re-edition of the propaganda and electoral proposal of a left that does not betray in a radicalization of demarcation in movements and unions, even with public party currents (in student, women mobilizations, CGIL, ecc), never practiced when it had dimensions and interventions far more significant than today;

- SA (Anticapitalist Left, USFI) with the compulsion to repeat the attempt to agglutinate the centrist left regardless of its Stalinist matrices and the assumption of popular perspectives, continuing to chase political projects that do not belong to it only to be promptly discharged (from Potere al Popolo to the cartels with the PRC/PCI);

- SCR (Left, Class, Revolution, the Italian organization of IMT) with the re-edition in struggles and movements of practices of party fractionalism, on the one hand with an action focused on the propaganda of its materials, on the other hand with the inability to take on any path of a united front or unity of action (even when participating in electoral lists or union areas).

The re-emergence of new large mobilizations (Nonunadimeno, Pride, FridayForFuture, or the Roman student’s movement, the Lupa, that sudden re-ignition of a wide student mobilization) in our impression replicated the occasional and inter-class dynamics that marked the last decade (from OccupyWallStreet to the Indignados): they represented more a sign of the current class decomposition than an opportunity for its relaunch. Rather, we saw in other dynamics still confined to the wide vanguard and that political sphere the announcement or occasion for possible new developments:

- Firstly, #insorgiamo, that is, the capacity of the GKN factory collective in Florence, around its dispute and the occupation of the plant, to activate not only broad territorial solidarity, not only a renewed attention in the widespread left on labor and conflicts in production relations, but also a convergence proposal that at least for a year represented, in fact, the only occasion for unitary mobilization of the broad social and political vanguard of the country (demonstrations in Florence in September 2022 and March 2023, 15-20 thousand participants capable of bringing together grassroots unions, leftists, CGIL sectors, FFF and student circuits, antagonistic, centrist, and revolutionary but also sectors of the reformist left and CGIL, albeit sporadically). In fact, in a terrible season of division, they built a class united front perspective even without managing to articulate it over time in territories and practices.

- Secondly, hints of possible confrontations and recompositions in the vanguard: the initiation by SiCobas and TIR of coordination paths (first the assemblies of combatants and then the hint at an anti-imperialist disbanding front with the assemblies in Rome and Milan); the opening in Sinistra Anticapitalista of a dialectic on its strategy; the attempt by SGB, once the unification with CUB failed, to play a unitary and fluid role in the asphyxiating relationships of grassroots unionism; the complicated survival of an alternative current in CGIL despite the landinist wills, the wear and tear of the broad fabric of delegates, and the absence of mass movements.

4- The dynamics of reality have been different. We formed a few weeks before February 24, 2022, the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In that conflict, we witnessed the division of the Eurasian continent, the direct confrontation between weak and strong imperialisms (EU/Russia; USA/China), and the emergence of a new season of frictional imperialism (a clash between global poles that, still unprepared for a global war and fearful of the nuclear threat, weave international blocs, begin mobilizing their economies and societies, and attempt to contain one another). This new season not only brought the shadow of a global war back into the perspective of European populations but exacerbated a new inflationary cycle and reignited reactionary strategies and movements. This season thus impacted mass processes and class struggle as well as the broad vanguard and therefore its political dynamics, multiplying uncertainties and divisions. In fact, at the end of this biennium, the same faint signs of a possible new season of social conflict assumed contradictory values.

- On the continental level, we saw a resurgence of labor conflicts. An acute and prolonged inflationary peak began before the Ukrainian war, due to the imbalances of the crisis and the post-pandemic rebound, and it was exacerbated by the conflict. This peak triggered a new season of widespread economic strikes in Europe, in which the impressive French movement against pensions last year marks a significant resumption of large mass political movements. Both phenomena were significant even if in some way both were marked by contradictory dynamics: wage strikes were divided not only by country but also by categories, with few general strikes that were not very successful (even compared to the 2010/12 season), a mobilization concentrated only in certain sectors (transport, logistics, and public employment, particularly health and education); the French movement saw large mass participation in the parades and their unprecedented territorial diffusion, but poor impact in workplaces and strikes; an inter-union direction with renewed centrality of work but little capacity for mass self-organization.

- In Italy, this dynamic did not manifest itself either in mass initiative or in strikes. In fact, the rise of Meloni’s government and its reactionary policies did not trigger large political marches, unlike other realities on the continent (the large demonstrations against Afd in Germany, the French reaction to the possibility of a Le Pen government, the mobilization in England that this summer extinguished the attacks against immigrants). Although there were large participations in pride events or in reaction to the femicide of Giulia Cecchetin (a young woman, university student, butchered by her finacè), a mass opposition has thus far been lacking. The main responsibility lies with CGIL, which did not want to trigger a reaction to the victory of the right (demonstration of 10.9.2022) and called for disjointed and late strikes (December 22 and 23), later shifting the initiative to the referendum ground. Thus, even if there have been successful strikes (health, Trenitalia, and railways, wood, and furniture, etc.), they remained occasional, not even marking the start of a new cycle of struggles. Rather, the cycle of logistics in the Po Valley, which has marked the last decade, begins to feel the impact of the strategies of internalizations and relocations initiated by employers, slowing down its union dynamics. The closure of major private contracts in the last two years within a framework of categorical fragmentation (differences in increases and salary mechanisms) but of union unity (despite the harsh confederation confrontation between CGIL, CISL, and UIL) the substantial division and marginality of grassroots unionism and the embarrassing silence of public sectors marked a season that has continued, if not aggravated, the retreat of labor.

- The broad social and political vanguard saw the closure of the spring of convergence. The dynamics of #insorgiamo wore out in the substantial defeat of the GKN dispute (with a bogged-down hypothesis of reindustrialization and survival strategies centered on sustainable cooperation). No social or political reality has been able to replace its role. The mobilization against the genocide in Gaza, beyond the widespread logic of a national liberation front (even with reactionary and fundamentalist forces), did not see the repetition of the Milan initiative last February (a demonstration of over 20 thousand participants that brought together the entirety of the various lefts) and developed through limited, combative, and determined student actions but marked by extreme competition among organizations and by the inability to give themselves a mass projection [also resulting in absurd accusations against Lotta Comunista in the absurd attempt to exclude it from universities and its senseless muscular reaction]. Thus, today yet another autumn unfolds with various and parallel mobilizations (October 5 on Palestine with evident vanguardist dynamics; October 11 FFF; October 12 school demonstration in Rome by Cambiare Rotta, USB, CUB, and the divided ensemble of Cobas school, in addition to the dispersed march of the Palestinian community; October 18 national SICobas strike on security bill and Automotive FIOM FIM UILM; October 19 public demonstration CGIL and UIL; October 26 demonstration against the war Europe for Peace and Italian Disarmament Network; October 31 general strike USB public employment; late October likely knowledge strike FLC CGIL; late November CGIL and UIL strike). This dunamic reproduce a season of confrontation more than launching a new phase of permanent social conflict. Conflict bubbles are produced, as we have called them in recent months, which we try to navigate and hope do not explode, disappearing into nothingness.

- Political dynamics in the vanguard have thus seen further sectarian fragmentation. The condition of mass struggles and the broad vanguard has weighed on the Italian left. Reformist sectors (Alleanza Verdi Sinistra: Alliance Green Left) were able to capitalize on the electoral (and thus political) terrain the role of a parliamentary anti-fascist and ecological force [reaching 6.78% and 1.5 million votes in the European elections]. It didn’t crush spaces to its left [Pace Terra e Dignità 2,1% and 500 thousand votes, both in percentage and in absolute votes more than Unione Popolare and PCI in the 2022 political elections]. Despite this, the alternative left has deepened its identity dynamics. Each subject, however reduced and minority, today presents itself as a possible center of reaggregation, each outlining its own paths in often sectarian dynamics, canceling not only the perspective of a mass united front (capable of converging and involving even reformist forces), canceling not only the practice of unity of action but canceling sometimes even that necessary inter-group coordination for the safeguarding of mobilizations. In this drift, the lines of fracture multiply between and within the different subjects (contradictory strikes in grassroots unionism; the congress fracture of PRC which produced a de facto double organization; the perennial dualism in PaP; the antagonistic kaleidoscope; the division of Cobas school, etc.) while the compulsions to repeat some components sharpen: the sudden and ill-advised construction of lists without identity and roots in labor (Pace Terra e Dignità); a Togliattian political offer in sixty-fourths (PCI); the eternal pendulum of unitary and vanguardist proposals destined for cyclical organizational closures (SiCobas today against the security bill); proposals for a united front but only for the vanguard (the Front of the Communist Youth); demarcation and electoral presence (the PCL in Rome, Pavia, and Liguria; in CGIL or among students); the construction today, twenty years late and in a historical retreat, of an International with independent parties (SCR with the IMT that radicalizes its organizational practice in PCR/ICR). The only sign of novelty, in some ways, are the signals of thawing of the strategic waiting of Lotta Comunista (today probably the subject with the broadest militant structure in the Italian left): the precipitating of world competition and the crisis of order (to use its language) with the possible development of global conflicts closes that season of retreat of revolutionary forces in front of American and Stalinist hegemony. This change, however, remains, to date, substantially confined to analysis with some signs of willingness for confrontation and intervention (solidarity in neighborhoods and revendicative demonstrations) without undermining its posture (focusing on propaganda, no articulation of a transitional method, incorporation into the CGIL majority).

- The distance between mass dynamics and the vanguard. The last two years marked by the precipitation of friction imperialism (the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the conflict in Gaza, and the growing Chinese development) have thus seen the bubbles of social struggles multiply, the fractures of the broad vanguard, and the confrontations in the more militant one. Thus, a rift has consolidated and widened between the representations, imaginaries, and lived experiences of the masses and those of the so-called vanguard. On the mass level, the experience of the proletariat is marked by particularisms with partial and simultaneously absolutist identities. This dynamic leads to the development of fragmented and dispersed mobilizations but also to multitudes (who consider themselves alien and transversal to the conflicts in production relations). These movements sometimes are anti-system and very radical (contesting the existing state of affairs but interpreting capitalism as a political superstructure, a command and not a relationship between social classes), but they represent themselves as classless and they articulate themselves in fluid forms without widespread structures. In this context, the mass experience suffers the fascination of building large political alliances, popular or democratic fronts to counter repressive straits and reactionary threats, having no widespread consciousness of the antagonism of class interests and not even the prospect of building a social bloc of subordinate classes. Hence arises, on the one hand, the penetration of reactionary voting in the proletariat and even in organized working-class sectors, which meets the experiences of anger and fear, as well as the illusion of a response to their specific conditions. On the other hand, it arises widespread consensus for the New French Popular Front and the democratic alliance against Le Pen, voting in Italy for AVS and even for Schlein’s PD, the apparent inevitability of the perspective of a campo largo (the broad field, the name in Italy of a larga democratic alliance of PD, 5 star movement, the reformist left of AVS and other liberal subject). On the level of the vanguard, the experience of political and social left activists takes place mostly in an abstract dimension disconnected from specific contexts, without rooting and representation of the different layers or class sectors, proposing therefore self-centered and sectarian practices that we have seen on one hand pursuing mass processes lived mostly as alien and incomprehensible, on the other driven by the anxiety to distinguish themselves from other programs and settings. We find ourselves, then, eighty years later, still swimming against the current, this time not in relation to the social-democratic and Stalinist hegemony in an organized class, but in relation to the awareness of the importance of class independence and the united front in a disorganized and dispersed working class.

5- Meanwhile, the reactionary right has consolidated its government. Fratelli di Italia (Brothers of Italy) has built its mass ascent on the processes of the last fifteen years: the Great crisis and the divergence of intermediate layers with sectors of the small and medium productive bourgeoisie (productive districts), commercial (small shops), and professional (old and new trades) threatened in their very reproduction due to the reduction of profit margins (competition in markets and centralization of capital) or the expansion of valorization circuits (development of professional service companies); the integration of world markets with the spread of mass migrations, the consolidation of multicultural societies, and the development of global cultural traits (from Netflix to Spotify) that triggered xenophobic and nationalist reactions; within this global culture, particularly among the younger generations, a questioning of gender roles and dominant sexual cultures with the victories of gay/lesbian rights and the development of the LGBTQ+ movement that triggered traditionalist and patriarchal reactions; the de(com)position of the left populace in the context of a general class disorganization; the emergence of a reactionary movement alien to the right (the 5 Stars) capable of disrupting traditional affiliations and penetrating new intermediate classes with a strong youth presence; the yellow-green government that, in its 15 months, legitimized a xenophobic common sense that consolidated reactionary consensus (almost a third in society, over 40% of votes); the transformation of the 5 Stars into an ambiguously progressive force that led a part of the consensus to the right; the national unity government of Draghi that highlighted Meloni as the main opposition to liberal policies (condensed in the PNRR as the founding reason and hallmark of that government). Brothers of Italy, therefore, today gathers a request for a different capitalistic management of the nationalist and community crisis with the ability to penetrate subordinate classes (see the vote in Terni, Piombino, or Roman suburbs) and produce common sense (especially if unchallenged), even if it is still a minority in the country. It governs in any case with a broad parliamentary majority and a solid alliance although it suffers from competition from Salvini (and his temptations for radicalization like Vannacci) and a difficult relationship with Forza Italia’s Europeanist impulses. The underlying limits of its policy are actually elsewhere:

- The difficulty of practicing a different capitalistic management of the crisis: despite its consensus in intermediate classes and popular sectors deriving from this. Its nationalist and community framework alluding to a war policy focused on public intervention, rearmament, and blocking strategies (perimetering of markets) in tune with the dynamics of friction imperialism. However, such a passage has not (yet?) developed in the concrete arrangements of our social formation (Italian and European). The core nuclei of big capital do not intend to abandon the neoliberal accumulation strategy of recent decades (hyper-financial development, widespread debt, market integration, and pressure on wages) until they are forced to do so. Moreover, a new nationalist management of the capitalist crisis in the context of current friction imperialism to be effective would need to develop on continental dimensions, while the reaction of intermediate classes in their gaze at an ideal past never lived is directed towards the motherland’s borders, if not to narrower dimensions (see the League and the industrial north connected to the European core).

- Here lies the main contradiction of Meloni’s government. The European Union, although still under liberal traction, is deeply marked by different elements: divisions among the different fractions of big capital regarding the need to tighten the Atlantic alliance or develop a continental imperialist arrangement; the weakness of European big capital, with the hypotheses for building a supporting core on credit, energy, infrastructure, and defense (see the Letta and Draghi plans); resistance to developing a federal budget and a continental public expenditure (even just for rearmament and strategic infrastructures); centrifugal trends that now not only dominate peripheral realities (from Hungary to Austria) but also press on the central European core (France and Germany). The war in Ukraine, the rupture of the German capital’s Eurasian strategy (explosion of Nordstream, closure of direct connections between the EU and China through Russia), and the wear of an export-centered economic policy deepened the institutional and political crisis of the Union (a parliament without a clear political majority and a Commission unmoored from the two central governments on the continent). In this situation there is no room for either a different capitalistic management of the crisis at the continental level or for addressing it within a single country.

- This contradiction therefore manifests itself in the inconsistencies and difficulties of governance. The problems do not lie in the endless missteps and numerous gaffes of its team (the Meloni sisters and their ex-partners, the deputies with guns, the undersecretaries disseminating confidential documents, the Ministers who make their employees work on redundancy, who stopped trains for their affairs, and who cry on TV for their mistresses). The problems are in the double soul on the European stage (to the right but in support of the Commission), in the reactivation of the Stability Pact [which imposes stringent limits on the budget policies of the next seven years], in the need to agree on strategies and fundamental strategic choices with Blackrock [the largest investment company in the world, present with significant stakes in the country’s main banks and industries, both private and public]. If fiscal pardons may be sufficient to maintain a grip on intermediate classes, the Europeanist inconsistencies can irritate significant sectors of the ruling classes, and policies of cuts and sacrifices may wear down popular consent.

- In this framework, the hypothesis of an authoritarian tightening matures. We are not only faced with an ideological propensity of sectors that have never abandoned their fascistoid culture, which emerges in some provisions (the rules on Rave, Conduct Vote, or Security). We are facing the strategic hypothesis of exiting these contradictions through a real bonapartist turn [like the one Berlusconi alluded to without ever having the strength to try it; like the one Renzi attempted without managing to conclude it. That is, the autonomization of political power (from the necessity of majority consensus and the need to respond to a reference social bloc) to use the state’s apparatus and its economic control to redraw the arrangements of the productive structure and thus its social organization. The temptation is, in other words, to build a regime that can somehow seize the times’ trend and create a new season of crisis management. It is not a simple passage: not so much due to this disorganized ruling class (after all, the fascist class behind Mussolini was not different in either familism or buffoonery) but due to the absence of a social emergency (a red threat as in 1921) or an international collapse capable of giving it the decisive strength to prevail. In fact, the tightening, just like in Renzi’s time, could coagulate political and social oppositions in the referendum dynamics, leading to its defeat. The option of constitutional reform and the premiership is not coincidentally postponed to better times today.

- The current parliamentary opposition, however, is divided. What matters is not just the protagonism of specific figures (Conte, Calenda, Renzi, Schlein), which undoubtedly plays a role in daily news coverage and the sequence of political events. What matters is the fragmentation of the ruling and subordinate classes in the country: the absence of a stable arrangement in big capital, the divergence between the submerged and saved in intermediate classes, and the pulverization of the working class. Thus, while the Right manages to agglutinate on a nationalist and reactionary discourse the intermediate classes frightened by the crisis, the retrograde sectors of big capital, and a part of the disaggregated popular sectors, the oppositions are separated by contradictory strategies: the persistence of liberal and Europeanist policies, The aspiration to a neo-Keynesian proposal that lacks substance and perspective (for the same structural reasons that make it difficult to initiate a different capitalistic management), the chasing of themes and imaginaries capable of penetrating the center-right electorate. Thus, the so-called campo aperto (the democratic alliance of the parliamentary opposition) is not only traversed by competitive dynamics (particularly between PD and 5S) but by opposition in parliamentary votes on the EU, evident differences in foreign policy, uncertain and mutable alliances in local elections. It manages to recompact itself only to counter the Right as it did on next referendums about labor, differentiated autonomy (regional federalism), and citizenship, despite the different merits.

- This political year will therefore be marked by the referendums vote if the most significant questions survive the scrutiny of the Consulta (especially the repeal of the Calderoli law and citizenship). The characteristics of the referendum vote indeed facilitate the re-composition of the opposition against a non-majoritarian government front in the country, while the questions hit the cornerstones of current reactionary politics (even if only on the political level because the Calderoli law regulates but does not determine the differentiated autonomy foreseen by the constitutional revision of 2001; the reduction to five years of citizenship does not change its census approach and thus does not significantly widen it; the questions on causal layoffs, precariousness, and contracts have little impact on the reality of things). An eventual defeat with the achievement of a quorum could then mark the future of the government starting from the continuation or not of the reactionary tightening with the constitutional reform. For this reason, Meloni will likely play the referendum campaign on her person, taking the referendum package as a whole as a symbol of the opposition’s policies, while the opposition on one side will be tempted to respond on the same level (weaving a democratic front against the right), and on the other will try to chase an opinion on the merits that has broader boundaries than its alignment (especially in the South on autonomy and in the North on citizenship, due to the high presence and integration of migrant communities).

- The main risk is that once again the opposition between capital and labor does not emerge. The scope and penetration capacity of the questions promoted by CGIL is low (as shown by the same dynamics of signature collection, with a goal achieved more due to the strength of the organization than viral adherence in the population), and thus the dimensions that risk prevailing in communication, in the imaginary, and in social representations are those of civil rights, the territorial division of the country, and the opposition between the democratic front and the Right. A dynamic that risks favoring Meloni herself because to bring over 23 million people to vote would require not only southern participation against differentiated autonomy, not only that of the metropolitan and progressive sectors of the North but also that of those popular and working-class sectors that in industrial areas risk suffering more heavily from the territorial division of universal rights, the logic of budgeting, and the privatizations underlying differentiated autonomy. In any case, precisely in this season, it becomes crucial to underline the class point of view in the political clash starting from the development of a mass social opposition against the budget law and the cuts that will be decided in the upcoming season (health, pensions, education, etc.).

6- A small boat in a terrible current [Fighting against the stream, Trotsky 1939]. We have traversed these two years in the bubbles of social conflict and in the verification of possible paths of reaggregation, trying to keep open the perspective of a communist and revolutionary project focused on class independence and internationalism. On one hand, we have adopted a position of bilateral disengagement in the Ukrainian conflict, acknowledging the scale of the clash between dominant imperialisms. On the other hand, we have reaffirmed support for the Palestinian resistance after October 7, while explicitly rejecting any notion of a national liberation front and any leniency toward Hamas, its reactionary agenda, and its related methods of struggle. In this context, we have revisited the proposal for the de-Zionization of Israel, and the critique of armed struggle methods advocated by Matzpen in the 1960s and 70s. This setting confirmed the divergence with the PCL: within the framework of its verticalist and vanguardist drifts, it adopted positions (sometimes contradictory) of support for the Ukrainian resistance and emphasis on Palestinian mobilizations, thus starting a path of international regrouping with the League of the Fifth International and the ISL with similar political positions. In this transition, we set ourselves a more functional site for communication and continuity of reasoning through a magazine (ControVento), which we tried to give periodicity every 5/6 months, arriving at an official registration and producing five issues (November 2022; April 2023; October 2023; April 2024; October 2024). At the same time, we tried to be present in the most significant mobilizations with our point of view, we built periodic online appointments and initiatives, we initiated an international confrontation path (in the Conferences in Milan and beyond). In these two years, we have also developed opportunities for confrontation with other subjectivities, to verify possible common paths and also hypotheses of progressive reaggregation. The dynamics of things, the strength of the current and fractures in the vanguard revealed the sterility of most of them. The minority of Sinistra Anticapitalista divided over Ukraine (between sectors very close to our perspectives like Brescia anticapitalista and others that have adopted positions of full support for Ukrainian resistance) and progressively realigned with the majority on political strategies (enough to conclude the last congress jointly): so, we interrupted de facto every relationship. TIR and SiCobas, beyond their fluctuating postures, developed a position of full support for Palestinian resistance and its political unity, nullifying that convergence that had developed on the Ukrainian question. The meeting with other small realities of the Trotskyist diaspora (from Occhiodiclasse to the CheGuevara Collective) revealed significant differences in approach. In respect of the plurality of positions and paths of the Association, in the face of the fragmentation of the working-class, our comrades in Bologna posed the problem of re-composing the resistance elements present in various forms in the territory, promoting the experience of Sinistra Unita for Bologna, first an alternative list to the Pd for the municipal council and neighborhoods, then transformed into a city coordination aggregating parties but above all comrades without affiliations. The goal of developing a plural political space to regroup forces on a programmatic basis continues and has developed relationships in other territories, albeit clashing with ongoing processes in the left and with the difficulty of giving national forms to this path. In any case, in these two years we have developed a collaboration of initiatives with ControCorrente/Puntocritico.info, based on a similar vision of the new international season and its conflicts, from parallel reflections (even if not overlapping) on the limits and crisis of the historical path of revolutionary communism to a common attention to the dynamics and organization of class conflict (initiatives on the war in Ukraine, on the presentation of Mandel’s book about the second world’s war, on Amazon and on the working poor, on the USA and its conflicts, on the European right, on militarization in schools and universities). However, this path is limited by three evident diversities that make it difficult to develop this relationship: firstly, the different propensity on the political-organizational terrain [their assessment that the opposing current of this phase can only be faced as a structure of analysis and chronicle without expressing complete political subjectivities today]; secondly, the different relationship with Lotta Comunista and its intervention; thirdly, the different reasoning and different placement in the union intervention. Despite these evident and conscious diversities, the converging analysis on the international situation and the importance of developing anti-imperialist, disbanding, and anti-militarist interventions today, as well as the similar attention to conflicts in production relations, are grounds for continuing to develop common initiatives on these shared elements in a specific perspective of unity of action.

7- Sometimes the only way to walk straight is to change the road [Ken Parker, Native American No. 26]. The different dynamics of things compared to our expectations, the new political season initiated by the war in Ukraine; the persistence and indeed the deepening of the divisions between mass dynamics and vanguard; the objective difficulty in developing new paths of reaggregation in this context; the emergence of a new political generation that on the one hand does not have the lived experience of the mass left of the past and on the other lives the current season of fractures and sectarism: all this raises the necessity for a change in ControVento. The transitoriness of its path after more than two years of life must be rationalized. We are aware of being out of date, that is, to move from a programmatic framework and a political practice today against the current compared to the experiences of the broad masses and the perception of the broad political and social vanguard. First of all, as we have highlighted, on class independence and the role of the united front. However, precisely in the face of the new season of war and the rise of the right, it is necessary to consolidate our small lifeboat and prepare for a prolonged navigation against the current. For this reason, the following steps are proposed in this 2024 assembly of AMR ControVento.

- Build a political collective. To navigate this current, it is necessary for the association to be able to initiate a true political and organizational leap. We must, that is, despite the limitations of our forces, try to focus and coordinate our action in addition to providing ourselves with a daily intervention. Of course, we do not want to reproduce another micro-organization that thinks of itself as the central place of reorganization of the vanguard and the initiation of a revolutionary process by retracing practices and construction methods that we consider deleterious. We do not want to renounce the founding characteristics of our programmatic path but also of the elaboration and experimentation of political practices. However, ControVento must give itself a capacity for collective proposal and intervention, overcoming its current configuration as a political magazine and meeting place for militancies. In the awareness that our dimensions and our dispersion make a full organicity of action complicated, it is necessary in any case to give ourselves a common practice that does not limit itself to a shared programmatic framework but can identify priorities, methods, and interventions carried out collectively. Only in this way can we think of surviving while interfacing with mass conflicts and political processes of the vanguard. This is an organizational passage but primarily a political passage.

- Define a political proposal. Building a collective practice means giving ourselves a complete proposal that today, starting from our programmatic framework and our analysis, can only be articulated on three main axes: the united front of the class; the unity of action of the classist and internationalist left; the construction of a class political and electoral pole.

- The united front of the working class: in a context where the global economic crisis is worsening, unemployment is increasing, and international capital has launched a systematic offensive against workers in almost all countries… a spontaneous and literally unstoppable tendency towards unity has awakened… The new politically less experienced layers awakening to active life dream of the union of all workers’ parties and all workers’ organizations in general and hope to increase their capacity for resistance against capital in this way [Thesis on the united front, Executive Committee of the Comintern, December 18, 1921]. The united front was thus explicitly conceived as unity in action among all left political forces and unions of all orientations to unite labor against the bosses’ and reactionary offensives, without nullifying articulations and programmatic differences but constructing a common field in which these can confront and compete. Revolutionary communists, that is, see themselves as part of a vanguard that acts to win the majority of an entire class and thus also to build moments of reunification of the entire working class (mass movements) and its self-organized structures (councils or in any case representative movement structures). This today means committing to support moments of struggle (strikes, demonstrations, mobilizations) capable of uniting the multitude of work, the entirety of its social and political subjectivities. This means on one side contrasting the vanguardist readings and the operations of fracture of mobilizations, while on the other engaging so that in inter-class movements (anti-fascist, feminist, environmental, etc.) the different viewpoints and class fractures emerge clearly.

- Unity of action of the classist and internationalist left. Fighting for the mass united front also means trying to build within this united front a classist and revolutionary polarization: that is, when mobilizations, movements, or dynamics develop in which there is a wide representation of the political and social subjectivities of the proletariat, it is important that in these contexts the classist and internationalist approaches gain visibility, weight, attraction capacity, and also direction, those that support perspectives of independence and international unity of the working class. Given the broad fragmentation of the current Italian left but also the widespread charm and broad influence of Stalinist, Negrian, neo-Keynesian, or confusedly neocampist traditions, it is indeed important to actively contrast trends that develop in struggles of economicist, reformist, populist, nationalist, or somehow neocampist origins (which consider a dominant imperialism and support any alternative force or field, whether supported by minor imperialisms, nationalist forces, or fundamentalist regimes). Given the overall weakness of revolutionary or centrist left perspectives, it is useful for those who share these common denominators (beyond different traditions, programs, or political settings) to try to coordinate to together polarize mass dynamics or large vanguard ones.

- The working-class pole. In the face of the disarray and decline of the left, it might be useful to revisit the political proposal that characterized the PRC left in the 1990s, adapting it to today’s context: the working-class pole. Today, it is necessary to rebuild an organized political presence of the working class, including as an electoral front, because in a period of social fragmentation, the political arena influences collective imaginaries and identities. The working-class pole is an algebraic political formula that emphasizes the need for an independent political presence of the working class, as an alternative to every progressive pole or alliance. Its articulation can vary greatly. In the 1990s, it underscored the need for a break between the PRC and the center-left, opposing the positions of the majority (Bertinotti and Cossutta). When the PCL (Workers’ Communist Party) was founded, the party viewed itself as the class pole (“the left that does not betray”), without feeling the need to articulate other political or electoral proposals. At the PCL’s second congress (2011), however, an amendment was proposed (supported by 33% of delegates, with 19% abstaining) stressing that the party’s construction should not be self-referential but should respond to the political tasks of the phase. Although elections under bourgeois regimes do not directly challenge the ruling class’s power, they hold objective value, particularly in times of acute crisis; they can influence the dynamics of struggle and the balance of power between classes. The presence, proposals, and results achieved by a party shape its perception and credibility in the eyes of the masses. This opened the possibility of revolutionary, class-based electoral alliances or coalitions in which the party’s role would be clearly identifiable: a proposal partially realized in the 2018 elections with the “For a Revolutionary Left” list. Today, this formula calls for a political and electoral pole that clearly aligns with labor, opposing reactionary right-wing forces and broad alliances alike, rejecting both nationalist and liberal strategies. However, this proposal clashes with a left that resists such a perspective: the PCL pursues a vanguardist policy of self-representation; SCR has rebranded as PCR; SA tends to align with the decisions of major forces, which themselves aim at regroupments beyond the working class (PaP on a populist/popular front, PRC on a civic or generic front, such as “Civil Revolution” or “Peace, Land, Dignity”); AVS (Alleanza Verdi Sinistra, Alleance Green and Left), in the reformist camp, defines itself not only as part of the progressive field but also as a mere gathering of social movements and civil rights groups (as seen in recent European electoral lists). Proposing the working-class pole today means addressing the reconstruction of an autonomous and alternative political space for labor, which none of the current leftist forces truly embrace. In discussions within the ControVento Collective, while there is broad agreement on this general political proposal, debates remain open on its concrete implementation in this particularly regressive context and on the risk of its misinterpretation by both the vanguard and the masses, due to the confused political-electoral practices of the past decade.

- Strengthening organizational cohesion. The ControVento collective’s development must also be organizational. This involves, first and foremost, active participation and mobilization of members, enhancing their presence and capacity for elaboration (e.g., updating the website, improving social media, producing leaflets, organizing events, and publishing a journal). It means conceiving and structuring ourselves as a collective entity, identifying shared areas of intervention to focus our action. Based on our trajectory, two key areas stand out: the friction of imperialism (opposing social militarization and the reactionary right) and class conflict in production relations (examining its forms and cycles of struggle). Greater collective commitment may also necessitate a more structured political debate on tactical or strategic hypotheses and decisions within the framework of our shared programmatic foundation. Our foundational principles include a general commitment to democratic centralism as a means of regulating discussions. Free and equal debate among differing political positions is not an accessory element of our tradition and praxis; it is a response to the tragic experiences of the communist movement, including the authoritarian and Bonapartist distortions of the 1920s in the Soviet Union, the Third International, and all communist parties. The definition of political lines through the free and equal confrontation of different, even organized, positions is an essential safeguard against degeneration within the party and in its relationship with the working class [3rd PCL Congress]. In this transitional phase, however, ControVento has integrated various analyses, positions, and political orientations into its daily praxis. Today, it is deemed important to confirm this approach, maintaining broad engagement with diverse analyses, proposals, and positions (within a shared programmatic framework), fostering this dialogue both within the collective and in public debates (as was the case in several moments of the Bolshevik experience). This includes freely expressing alternative positions and adopting majority-based political orientations where necessary. Within this framework, it is considered useful to entrust the Executive Committee with full responsibility for the management of the journal, website, and communication tools (political editorial board), while organizing periodic assemblies of the Association, ideally monthly.