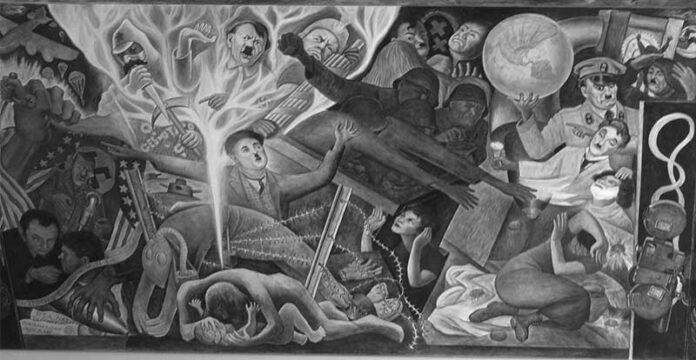

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor in Germany on January 30, 1933. On this occasion, we publish a text written by the painter and left-wing activist Diego Rivera. Rivera makes recollections of his visit to Berlin prior to Hitler’s rise to power. They are very valuable in exposing the inadequacy and sort-sightedness of the leaderships of the communist parties at the time.

While the fascists were gaining influence and were posing a deadly threat to the workers’ movement, the leadership of the German and the other Communist Parties, by now under the complete control of the Stalinist bureaucracy, were acting in the most outrageous way. They were denying the creation of a united antifascist front with other forces in the workers’ movement, they were considering the social-democrats to be a bigger threat than Hitler and they were convinced that after the Nazis it was their turn to come to power.

All these features that are vividly presented in Rivera’s text can also be found in the political documents of the Comintern. Trotsky and the forces around him decisively fought against this suicidal policy. Unfortunately, they didn’t have enough forces to influence the situation towards a different direction.

Today, the balance of forces is of course very different than in the ‘30’s. But still, we see the same political mistakes being made by sections of the Left internationally, who either underestimate the danger of the far-right and the fascists, or betray the working class and thus feed into their propaganda.

Either way, we need to take on board the lessons from the past in order not to repeat them in the future. We should strive to create united, broad, antifascist fronts to push back the neo-fascists. And link this fight with the struggle to overthrow capitalism, the system that breeds inequality, racist divisions, crises and suffering. No passaran!

HITLER

in Diego Rivera’s autobiography

My Art, My life

published in 1960

ON MY WAY, I stopped over in Berlin and did some interesting paintings there. My friend and host, Willi Muenzenberg, asked me many questions about my life and work, and my statements were incorporated in an excellent book by another friend, Lotte Schwartz. Entitled Das Werk Diego Riveras, this volume covered my career up to the murals I had just completed. It was published by the Neuer Deutscher Verlag headed by Muenzenberg.

In 1928, Germany was in the throes of a crisis that, in the next year, would become world wide. The big German cartels were slipping into bankruptcy, one after another. There was a wave of suicides among the bourgeoisie. Hugo Stinnes, head of the steel trust, Admiral von Tirpitz, a shipping magnate, and Dr. Scheidemann, boss of the chemical industry, all put revolvers to their heads and blew out their brains.

A contagion of lunacy was abroad in the land. I felt its presence on two separate, apparently unrelated occasions.

One night Muenzenberg, a few other friends, and I disguised ourselves and, with forged credentials, attended the most astounding ceremony I have ever witnessed. It took place in the forest of Grunewald near Berlin.

From behind a clump of trees in the middle of the forest, there appeared a strange cortege. The marching men and women wore white tunics and crowns of mistletoe, the Druidic ceremonial plant. In their hands, they held green branches. Their pace was slow and ritualistic. Behind them four men bore an archaic throne on which was seated a man representing the war god, Wotan. This man was none other than the President of the Republic, Paul von Hindenburg! Garbed in ancient raiment, von Hindenburg held aloft a lance on which supposedly magic runes were engraved. The audience, Muenzenberg explained, took von Hindenburg for a reincarnation of Wotan. Behind Hindenburg’s appeared another throne occupied by Marshal Ludendorff, who represented the thunder god, Thor. Behind the “god” trooped an honorary train of worshippers composed of eminent chemists, mathematicians, biologists, physicists, and philosophers. Every field of German “Kultur” was represented in the Grunewald that night.

The procession halted and the ceremony began. For several hours the elite of Berlin chanted and howled prayers and rites from out of Germany’s barbaric past. Here was proof, if anyone needed it, of the failure of two thousand years of Roman, Greek, and European civilization. I could hardly believe that what I saw was really taking place before my eyes.

Nobody among my German leftist friends could give me any satisfactory explanation of the bizarre proceedings. Instead, they tried to laugh them off, calling the participants “crazy.” To this day, I am puzzled by their collective lack of perception. Recalling that orgy of dry drunkenness and delirium, I found it impossible to imagine the least sensitive spectator dismissing what I had witnessed as only a harmless masquerade.

A few days later I saw Adolf Hitler address a mass meeting in Berlin, on a square before a building so immense that it took up the whole block. This structure was the headquarters of the German Communist Party. A temporary united front was then in effect between the Nazis and the Communists against the corrupt reformists and social democrats.

The square was literally jammed with twenty-five to thirty thousand Communist workers. Hitler arrived with an escort of nearly a thousand men. They crossed the square and halted below a window from which Communist Party leaders were watching. I was among them, having been invited by Muenzenberg, who was at my right. At my left stood Thaelmann, the Party’s General Secretary. Muenzenberg interpreted my comments for Thaelmann, and translated Hitler’s speech for me.

My Communist friends made mocking remarks about the “funny little man” who was to address the meeting, and considered those who saw a threat in him timorous or foolish.

As he prepared to speak, Hitler drew himself rigidly erect, as if he expected to swell out and fill his oversized English officer’s raincoat and look like a giant. Then he made a motion for silence. Some Communist workers booed him, but after a few minutes the entire crowd became perfectly silent.

As he warmed up, Hitler began screaming and waving his arms like an epileptic. Something about him must have stirred the deepest centers of his fellow Germans, for after awhile I sensed a weird magnetic current flowing between him and the crowd. So profound was it that, when he finished, after two hours of speaking, there was a second of complete silence. Not even the Communist youth groups, instructed to do so, whistled at him. Then the silence gave way to tremendous, ear-shattering applause from all over the square.

As he left, Hitler’s followers closed ranks around him with every sign of devoted loyalty. Thaelmann and Muenzenberg laughed like schoolboys. As for me, I was as mystified and troubled now as when I had witnessed the decadent ritual a few days before in the Grunewald. I could see nothing to laugh at. I actually felt depressed.

Muenzenberg, glancing at me, asked, “Diego, what’s the matter with you?”

The matter with me was, I informed him, that I was filled with forebodings. I had a premonition that, if the armed Communists here permitted Hitler to leave this place alive, he might live to cut off both of my comrades’ heads in a few years.

Thaelmann and Muenzenberg only laughed louder. Muenzenberg complimented me on my artist’s vivid imagination.

“You must be joking,” he said. “Haven’t you heard Hitler talk? Haven’t you understood the stupidities I translated for you?”

I replied, “But these idiocies are also in the heads of his audience, maddened by hunger and fear. Hitler is promising them a change, economic, political, cultural, and scientific. Well, they want changes, and he may be able to do just what he says, since he has all the capitalist money behind him. With that he can give food to the hungry German workers and persuade them to go over to his side and turn on us. Let me shoot him, at least. I’ll take the responsibility. He’s still within range.”

But this made my German comrades laugh still harder. After laughing himself out, Thaelmann said, “Of course it’s best to have someone always ready to liquidate the clown. Don’t worry, though. In a few months he’ll be finished, and then we’ll be in a position to take power.”

This only depressed me more, and I reiterated my fears. By now, Muenzenberg wasn’t smiling. He had been watching Hitler, then nearly at the other end of the square. He had noticed that the crowd was still applauding. Before leaving the square, Hitler turned and gave the Nazi salute. Instead of boos, the applause swelled. It was clear that Hitler had won many followers among these left-wing workers. Muenzenberg suddenly turned pale and clutched my arm.

Thaelmann looked surprised at both of us. Then he smiled wanly and patted my head. In Russian, which sounded thick in his German accent, he said, “Nitchevo, nitchevo.”—“It’s nothing, nothing at all.”

My “crazy” artist’s imagination was later bitterly substantiated. Both Thaelmann and my friend Muenzenberg were among the millions of human beings put to death by the “clown” we had watched in the square that day.