Around half (50.99%) of the 357 million voters in the 27 EU countries went to the polls for the European Parliament elections on 6-9 June 2024. The 51% turnout is an average, with participation varying widely from the lowest in Croatia (21%) and Lithuania (28%) to the highest in Belgium (89%) and Luxembourg (82%).

This figure alone gives us an idea of the situation. At a time of parallel and interlinked crises (stagflation, geopolitical rivalries and trade wars, climate crisis, wars in Ukraine and Israel-Palestine, etc.), European citizens have shown little enthusiasm for going to the polls and no particular interest in the outcome.

There are two main reasons for this. The first is that the European Parliament is essentially a decorative, non-decisive institution. In the eyes of the people, the European elections do not decide anything significant, which is why they mostly take on a “national” character, with votes cast according to “internal” criteria. The second and more important reason is that there is no serious political alternative offered. Establishment parties agree on the main lines of policy and only differ on minor details. The parties of the Left are, in their vast majority, hugely compromised, offering no perspective and no inspiration.

The Results

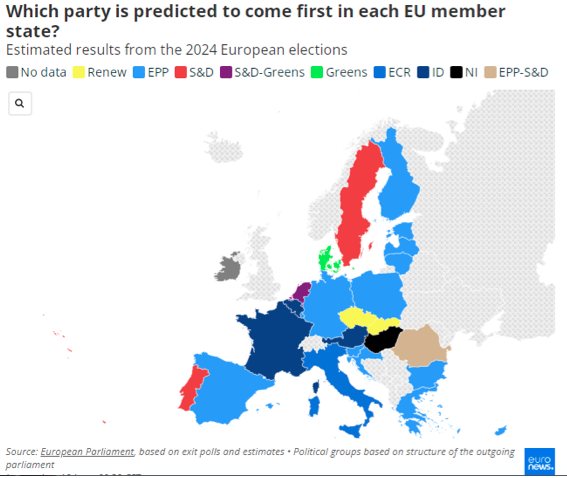

The results on a European level did not reveal any major surprises. There was a shift to the right in the make-up of the European Parliament, with the conservative European People’s Party (EPP) and Meloni’s “moderate” far-right European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) making gains. Also, the harder far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) group, which is led by Marine Le Pen, grew, although this is not recorded due to the fact that the German AfD (Alternative for Germany), which elected 15 MEPs, was kicked out. The Social Democrats remained stagnant, as did The Left.

If we add the seats of the main far-right parties in the European Parliament (ECR, ID, AfD, and the far-right parties from Hungary, Bulgaria, and Poland), we get 165 seats, or more than 22% of the seats. If the far right were to unite, it would be the second-largest group, just after the EPP.

The big losers in the European elections are the two smaller centrist parties, the Liberals (Renew Europe) and the Greens. The Greens paid the price for their proposals for a capitalist green transition (i.e., the logic that the poor should pay for dealing with the effects of climate change), as these policies made them hugely unpopular.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on election night that “The center is holding”. This is based on the fact that the parties in the majority so far (EPP, Socialists and Democrats, Liberals) have a majority of 400 seats out of 720, so they can continue to dominate the Parliament without having to bring either the far right or the Greens into their alliance. But this is only half of the story.

In reality, the far right is the only force with any momentum at the moment. Its increased strength means that it will be able to push harder for the implementation of the policies it stands for (be it the racist policies against refugees/immigrants, or policies of extreme environmental exploitation, repression, support for capital, and a conservative turn on social issues such as gender equality, abortion, etc).

The “centre” therefore “holds” in an unstable balance of power because it has no answer to the existential crisis the EU is going through (squeezed between the USA and the China-Russia axis). It has the slowest growing economy of the industrially advanced countries, and its political staff cannot offer any kind of vision to European citizens.

In the Member States

While there were no radical changes at the European Parliament level, the results in individual member states were more important. Here too, there were significant differences, and the trends were not the same everywhere.

In Spain, we saw the return of the “old two-party system,” with the right-wing People’s Party and the Socialdemocratic PSOE dominating, while the far-right Vox saw a significant drop in its share of the vote compared to last year’s general elections, receiving half as many votes (1.5 million compared to 3 million in 2023). A similar situation occurred in Portugal, where the two bourgeois parties dominated and the far-right Chega lost 8% and more than 700,000 votes compared to the elections earlier this year.

In Sweden, the Social Democratic Party came out on top, and the far-right Sweden Democrats lost 5% and half of their votes compared to last year. In Denmark, the Greens came first, while in the Netherlands, Wilders’ far-right party, which had topped the polls a few months ago, dropped to second place.

On the other hand, Austria’s Freedom Party (FPO), which until recently was in government and was ousted due to a scandal, came first again. In Belgium, the far-right Vlaams Belang (“Flemish Interest”) came first in the European elections but came second in the federal elections held on the same day, behind the “moderate” far-right N-VA (New Flemish Alliance).

In general, the trend that prevailed was the punishment of the government of the day. The ruling parties, whether right-wing, centre-left, far-right, or coalitions, everywhere pursue policies to the detriment of the working class and the poor. So, in the European elections, workers seized the opportunity to send a message of protest.

Germany and France

The most important developments were in Germany and France. The governing parties in both key countries in the EU imperialist bloc have been dealt a significant blow by the results.

In Germany, Scholz’s party came third, even behind the far-right AfD, while the other two parties in the ruling coalition, the Greens and the Liberals, saw their numbers fall (mainly the Greens, but also the Liberals).

In France, Macron’s alliance lost by a wide margin, with Le Pen’s party coming out on top with twice as many votes. This result led Macron to call early elections for the National Assembly in early July.

The results in Germany and France effectively weaken the EU’s leadership at a very critical time. With what “legitimacy” will Macron and Scholz be able to manage the very problematic internal situation of the EU, characterized by constant confrontations between member states, and foreign policy at a time of extreme international instability?

Macron has chosen to take the risk of going to the polls. In France’s electoral system, all 577 seats in the National Assembly are single-seat and a second round is held between the two most popular candidates of the first round. Macron will therefore try to play the “democracy against far right” card against Le Pen’s RN (National Rally).

But this card has been played before. Macron twice (in the ’17 and ’22 Presidential elections) won against Le Pen in the second round on the basis of this argument. But why is Le Pen still on the rise? Why have Macron’s policies failed to stop her? The answer is that it is precisely these policies that fuel the far right. Austerity, anti-worker attacks, racist measures, repression, a belligerent foreign policy, and support for Zelensky and Netanyahu create a suffocating mix that constantly feeds the far right. Thus, not only in France but throughout Europe, it is the “democratic” establishment parties that are responsible for the strengthening of the extreme right, however much they denounce it in words.

The “New Popular Front”

The left and center-left parties have already announced the creation of a New Popular Front against Le Pen and Macron in the run-up to the elections. This news will undoubtedly be welcomed with relief by a large part of the population who want to punish Macron but not vote for Le Pen. We should note, however, that a similar alliance (between the Socialist Party, the Greens, and Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise) stood in the last elections (under the name NUPES) but collapsed shortly afterwards.

The New Popular Front can act as a pole of attraction for large sections of the working class and put under question the electoral dominance of the French political scene by Marine Le Pen’s far right party. Also, some of its programmatical points, like a repeal of Macron’s pension reform of last year and a return of the pension age to 60, an increase in the minimum wage, increased expenditure on Education and Health, the recognition of Palestine as an independent state, etc, will naturally be attractive to large sections of the population.

However, the programme of the New Popular Front does not in any way question capitalism. This is its Achilles’ heel. Even if the NPF were to be in a position to control government policies, as long as capitalism survives there can be no solution to the problems of the French working class and the capitalist crisis – and this will bring back the far-right with a new dynamic. Only an anticapitalist/socialist programme can block the far-right’s rise to power, undermining its social support.

The idea of a united front of working class and left organisations against the far right on a grass roots basis has to be introduced very militantly and emphatically by the parties and organisations of the Left, particularly of the anticapitalist Left. Such a project must be based on local action committees, be characterized by democratic functioning, and aim to politically expose the systemic nature of the far right. At the base of society, not only in France but in all European countries, there are enough forces to form such a front. Striking trade unions, environmental movements, local movements on social issues, feminist and LGBTQ+ groups, organizations and parties of the Left, etc, can and must fight both the far right and the system that produces and sustains it. An anticapitalist/socialist programme is a necessary corollary of such a struggle – as this is the only way to defeat the far right on a long term basis.