Thodoris Marakis and Nikos Anastasiadis

Every year, on the anniversary of Lenin’s death (January 21, 1924), there are intense debates about his political testament.

As the key person behind the building of the Bolshevik Party and the strategy that led to the first victory of the socialist revolution, Lenin is widely respected and recognised by almost all forces on the Left. But when it comes to discussing his political testament, one of the last texts he dictated, Lenin’s “admirers” start being less clear in their support.

Let’s see what lies behind this controversy.

The text of the testament

But first let Lenin speak for himself. Here is the full text of his testament, which we will comment on below.

I

I would urge strongly that at this Congress a number of changes be made in our political structure.

I want to tell you of the considerations to which I attach most importance.

At the head of the list I set an increase in the number of Central Committee members to a few dozen or even a hundred. It is my opinion that without this reform our Central Committee would be in great danger if the course of events were not quite favourable for us (and that is something we cannot count on).

Then, I intend to propose that the Congress should on certain conditions invest the decisions of the State Planning Commission with legislative force, meeting, in this respect, the wishes of Comrade Trotsky- to a certain extent and on certain conditions.

As for the first point, i.e., increasing the number of C.C. members, I think it must be done in order to raise the prestige of the Central Committee, to do a thorough job of improving our administrative machinery and to prevent conflicts between small sections of the C.C. from acquiring excessive importance for the future of the Party.

It seems to me that our Party has every right to demand from the working class 50 to 100 C.C. members, and that it could get them from it without unduly taxing the resources of that class.

Such a reform would considerably increase the stability of our Party and ease its struggle in the encirclement of hostile states, which, in my opinion, is likely to, and must, become much more acute in the next few years. I think that the stability of our Party would gain a thousand-fold by such measure.

Lenin

December 23, 1922

II

Continuation of the notes

December 24, 1922

By stability of the Central Committee, of which I spoke above, I mean measure against a split, as far as such measures can at all be taken. For, of course, the whiteguard in Russkaya Mysl (it seems to have been S.S. Oldenburg) was right when, first, in the whiteguards’ game against Soviet Russia he banked on a split in our Party, and when, secondly, he banked on grave differences in our Party to cause that split.

Our Party relies on two classes and therefore its instability would be possible and its downfall inevitable if there were no agreement between those two classes. In that event this or that measure, and generally all talk about the stability of our C.C., would be futile. No measure of any kind could prevent a split in such a case. But I hope that this is too remote a future and too improbable an event to talk about.

I have in mind stability as a guarantee against a split in the immediate future, and I intend to deal here with a few ideas concerning personal qualities.

I think that from this standpoint the prime factors in the question of stability are such members of the C.C. as Stalin and Trotsky. I think relations between them make up the greater part of the danger of a split, which could be avoided, and this purpose, in my opinion, would be served, among other things, by increasing the number of C.C. members to 50 or 100.

Comrade Stalin, having become Secretary-General, has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution. Comrade Trotsky, on the other hand, as his struggle against the C.C. on the question of the People’s Commissariat of Communications has already proved, is distinguished not only by outstanding ability. He is personally perhaps the most capable man in the present C.C., but he has displayed excessive self-assurance and shown excessive preoccupation with the purely administrative side of the work.

These two qualities of the two outstanding leaders of the present C.C. can inadvertently lead to a split, and if our Party does not take steps to avert this, the split may come unexpectedly.

I shall not give any further appraisals of the personal qualities of other members of the C.C. I shall just recall that the October episode with Zinoviev and Kamenev was, of course, no accident, but neither can the blame for it be laid upon them personally, any more than non-Bolshevism can upon Trotsky.

Speaking of the young C.C. members, I wish to say a few words about Bukharin and Pyatakov. They are, in my opinion, the most outstanding figures (among the youngest ones), and the following must be borne in mind about them: Bukharin is not only a most valuable and major theorist of the Party; he is also rightly considered the favourite of the whole Party, but his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him (he has never made a study of the dialectics, and, I think, never fully understood it).

As for Pyatakov, he is unquestionably a man of outstanding will and outstanding ability, but shows too much zeal for administrating and the administrative side of the work to be relied upon in a serious political matter.

Both of these remarks, of course, are made only for the present, on the assumption that both these outstanding and devoted Party workers fail to find an occasion to enhance their knowledge and amend their one-sidedness.

Lenin

December 25, 1922

Addition to the above letter

Stalin is too rude and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst and in dealing among us Communists, becomes intolerable in a Secretary-General. That is why I suggest that the comrades think about a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead who in all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in having only one advantage, namely, that of being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite and more considerate to the comrades, less capricious, etc. This circumstance may appear to be a negligible detail. But I think that from the standpoint of safeguards against a split and from the standpoint of what I wrote above about the relationship between Stalin and Trotsky it is not a [minor] detail, but it is a detail which can assume decisive importance.

Lenin

January 4, 1923

III

Continuation of the notes

December 26, 1922

The increase in the number of C.C. members to 50 or even 100 must, in my opinion serve a double or even a treble purpose: the more members there are in the C.C., the more men will be trained in C.C. work and the less danger there will be of a split due to some indiscretion. The enlistment of many workers to the C.C. will help the workers to improve our administrative machinery, which is pretty bad. We inherited it, in effect, for the old regime, for it was absolutely impossible to reorganise it in such a short time, especially in conditions of war, famine, etc. That is why those “critics” who point to the defects of our administrative machinery out of mockery or malice may be calmly answered that they do not in the least understand the conditions of the revolution today. It is altogether impossible in five years to reorganise the machinery adequately, especially in the conditions in which our revolution took place. It is enough that in five years we have created a new type of state in which the workers are leading the peasants against the bourgeoisie; and in a hostile international environment this in itself is a gigantic achievement. But knowledge of this must on no account blind us to the fact that, in effect we took over the old machinery of state from the tsar and the bourgeoisie and that now, with the onset of peace and the satisfaction of the minimum requirements against famine, all our work must be directed towards improving the administrative machinery.

I think that a few dozen workers, being members of the C.C., can deal better than anybody else with checking, improving and remodeling our state apparatus. The Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection on whom this function devolved at the beginning proved unable to cope with it and can be used only as an ‘appendage’ or, on certain conditions, as an assistant to these members of the C.C. In my opinion, the workers admitted to the Central Committee should come preferably not form among those who have had long service in Soviet bodies (in this part of my letter the term workers everywhere includes peasants), because those workers have already acquired the very traditions and the very prejudices which it is desirable to combat.

The working-class members of the C.C. must be mainly workers of a lower stratum than those promoted in the last five years to work in Soviet bodies; they must be people closer to being rank-and-file workers and peasants, who, however, do not fall into the category of direct or indirect exploiters. I think that by attending all sittings of the C.C. and all sittings of the Political Bureau, and by reading all the documents of the C.C., such workers can form a staff of devoted supporters of the Soviet system, able, first, to give stability to the C.C. itself, and second, to work effectively on the renewal and improvement of the state apparatus.

Lenin

December 26, 1922

VII

Continuation of the notes

December 29, 1922

In increasing the number of its members, the C.C., I think, must also, and perhaps mainly, devote attention to checking and improving our administrative machinery, which is no good at all. For this we must enlist the services of highly qualified specialists, and the task of supplying those specialists must devolve upon the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection.

How are we to combine these checking specialists, people with adequate knowledge, and the new members of the C.C.? This problem must be resolved in practice.

It seems to me that the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection (as a result of its development and of our perplexity about its development) has led all in all to what we now observe, namely, to an intermediate position between a special People’s Commissariat and a special function of the members of the C.C.; between an institution that inspects anything and everything and an aggregate of not very numerous but first-class inspectors, who must be well paid (this is especially indispensble in our age when everything must be paid for and inspectors are directly employed by the institutions that pay them better).

If the number of C.C. members is increased in the appropriate way, and they go through a course of state management year after year with the help of highly qualified specialists and of members of the Workers’ and Peasants Inspection who are highly authoritative in every branch- then, I think, we shall successfully solve this problem which we have not managed to do for such a long time.

To sum up, 100 members of the C.C. at the most and not more than 400-500 assistants, members of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection, engaged in inspecting under their direction.

Lenin

December 29, 1922

The backstory behind the testament

Trotsky writes:

Toward the end of 1921 Lenin’s health broke sharply. On December 7, in taking his departure upon the insistence of his physician, Lenin, little given to complaining, wrote to the members of the Political Bureau:

“I am leaving today. In spite of my reduced quota of work and increased quota of rest, these last days the insomnia has increased devilishly. I am afraid I cannot speak either at the party Congress or the Soviet Congress.”

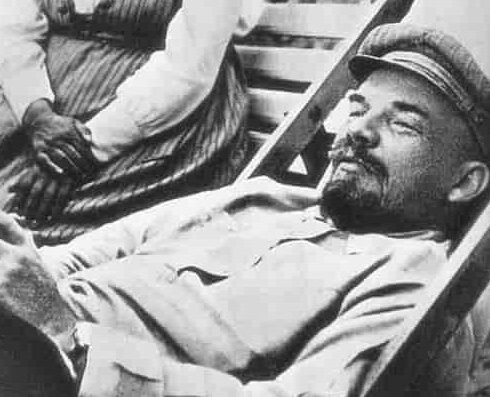

For five months he languishes, half removed by doctors and friends from his work, in continual alarm over the course of governmental and party affairs, in continual struggle with his lingering disease. In May he has the first stroke. For two months Lenin is unable to speak or write or move. In July he begins slowly to recover. Remaining in the country, he enters by degrees into active correspondence. In October he returns to the Kremlin and officially takes up his work.

“There is no evil without good,” he writes privately in the draft of a future speech. “I have been sitting quiet for a half year and looking on ’from the sidelines.’” Lenin means to say: I formerly sat too steadily at my post and failed to observe many things; the long interruption has now permitted me to see much with fresh eyes. What disturbed him most, unquestionably, was the monstrous growth of bureaucratic power, the focal point of which had become the Organization Bureau of the Central Committee.

Towards the end of 1922, Lenin’s health suffered another blow. He therefore decided to write his political testament. Lenin addressed this document to the 12th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which was to be held in April 1923. But after his third stroke in March 1923, the testament was hidden by his wife Krupskaya in the hope that his health would later improve. The document was given to the Politburo by Krupskaya after his death. Krupskaya conveyed Lenin’s demand that the document be released at the forthcoming 13th Party Congress in May 1924.

The majority of the Politburo refused to publish this important document! Only part of the testament was read to some delegates, divided into groups, and no notes were allowed to be taken! The testament was published outside the USSR in 1925 by the communist Max Eastman. Since then, and for many years, it has been banned in the Soviet Union and remained largely unknown in the West, at a time when the imperialists were beginning to come to terms with Stalin. They were particularly pleased that Stalin had abandoned the idea of internationalism and was building his bureaucratic “socialism in one country”.

After Stalin’s death, the testament was finally published in the USSR. The new General Secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, for his own reasons, used the testament to carry out the so-called “De-Stalinization” – an attempt to stabilise the regime getting rid of some of its most crude elements.

To this day, however, the document is not widely known.

The importance of the testament

The importance of this document cannot be overstated. Lenin clearly calls for Stalin’s removal from the post of General Secretary, and he more or less proposes to replace him with Trotsky, whom he considers, despite his shortcomings, “perhaps the most capable man in the present C.C “. At the same time, his proposals for enlarging the Central Committee are essentially directed against the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection, for which Stalin was responsible. When the text of the testament is combined with two more of Lenin’s last writings, the picture becomes clearer.

To: L. D. TROTSKY

Top secret

Personal

Dear Comrade Trotsky:

It is my earnest request that you should undertake the defence of the Georgian case in the Party C.C. This case is now under “persecution” by Stalin and Dzerzhinsky, and I cannot rely on their impartiality. Quite to the contrary. I would feel at ease if you agreed to undertake its defence. If you should refuse to do so for any reason, return the whole case to me. I shall consider it a sign that you do not accept.

With best comradely greetings

Lenin

Top secret

Personal

Copy to Comrades Kamenev and Zinoviev

Dear Comrade Stalin:

You have been so rude as to summon my wife to the telephone and use bad language. Although she had told you that she was prepared to forget this, the fact nevertheless became known through her to Zinoviev and Kamenev. I have no intention of forgetting so easily what has been done against me, and it goes without saying that what has been done against my wife I consider having been done against me as well. I ask you, therefore, to think it over whether you are prepared to withdraw what you have said and to make your apologies, or whether you prefer that relations between us should be broken off.[1]

Respectfully yours,

Lenin

March 5, 1923

In the first letter Lenin is essentially asking Trotsky to lead a political fight against Stalin, while in the second letter he is clearly attacking Stalin on the occasion of the Krupskaya incident.

The suppression of Lenin’s testament played its role in the years that followed. Stalin was able to consolidate power on behalf of the soviet bureaucracy and established a deformed workers state. Trotsky was exiled and eventually murdered. Any opposition was violently attacked. But Stalinism led the great Russian Revolution to an eventual defeat and the restoration of capitalism. On the occasion of Lenin’s death anniversary, it is crucial for all activists and progressive people to study this historical period and discuss ways to avoid repeating the same mistakes.