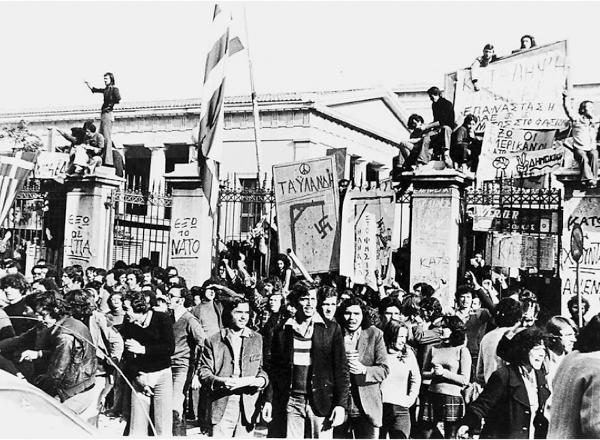

The Athens Polytechnic uprising of November 17, 1973, is a landmark moment in the history of the Greek movement. It was a massive revolt of students and workers which marked the beginning of the end for the military dictatorship (the hated Junta) of ’67.

On April 21, 1967, a group of colonels, supported by the CIA and big sections of the Greek ruling class, overthrew the elected government a month before scheduled elections. The far-right Junta imposed a hardline anticommunist regime in which all civil liberties were abolished. Trade unions were banned and the Left was crushed. Their leaders and members were imprisoned, tortured and exiled. Police and military repression were the order of the day. Ten thousand people were immediately arrested and concentration camps in remote islands were set up. Junta’s main slogan was Greece for Greek Christians.

Under these circumstances, anger and discontent was brewing inside society. And after a period of time, acts of resistance started to appear.

The first reactions of the students

The November ’73 uprising did not come out of the blue. The whole previous year was full of student mobilisations with militant characteristics and advanced demands.

The first big mobilisations by the student movement began on February 14, 1973, with a rally at the Polytechnic University demanding the repeal of Law 1347.

This law allowed enforced conscription for students engaged in student union activity. In this way the Junta targeted students who were organising struggles. The Greek army, even before the Junta but more so after, was tightly controlled by fascist elements who turned the life of progressive people to hell or tortured and jailed them.

To crush the resistance, police forces broke into the building of the Athens Polytechnic and arrested students; up to 100 were obliged to interrupt their studies and were forcibly conscripted.

A few days later, on February 21, 1973, the Athens Law School was occupied by students chanting slogans such as “Down with the Junta” and “Long live Freedom”. The police resorted to repression in order to stop the occupation. It was obvious that the occupation of the Law School was a precursor to what would unfold a few months later.

The November uprising

Resistance escalated with the events of the Polytechnic that took place on November 14-17.

On November 14, students gathered in the university’s campus at the centre of Athens, after having decided to abstain from classes. The general assemblies of the students then decided to proceed with occupying the building.

A number of students from other schools and workers also joined them and contributed to the organising next steps. A Coordinating Committee of the occupation was formed; it consisted of 22 students and 2 workers. The Coordinating Committee immediately radicalised the demands of the mobilisation, popularising the need to broaden the struggle for freedom, launching its main slogan “Bread – Education – Freedom”.

Committees were created in all the faculties for the better organisation of the occupation and the most important decisions were taken through student assemblies.

At the same time, an improvised radio station was set up in order to inform students and society about the struggle; this became the voice of the resistance and reached wider layers. A medical unit and a canteen were also organised for the needs of the people in the occupied buildings.

The uprising very quickly took on a mass character, with tens of thousands of people gathering inside and outside the Polytechnic, offering support and plenty of supplies, such as food and medicine, to help them continue the struggle.

The demand for the fall of the Junta and for freedom had mass appeal and was supported throughout the city.

The reaction of the Junta

Under the fear that the uprising would become a trigger that would overthrow their regime, the Junta’s reaction was to escalate repression and violence.

On November 16, the police attacked the people gathered outside the Polytechnic with water cannons and batons. Many of the demonstrators were hospitalised with injuries. Barricades were immediately set up to prevent the police forces from approaching the building.

This failed police intervention led the Junta’s leader, colonel Georgios Papadopoulos, to order the army to intervene to crush the revolt.

At the early hours of November 17, three tanks were placed outside the Polytechnic. One of them pointed its cannon towards the main gate. The Coordinating Committee asked for negotiations, but their request was not granted.

At 3 am, one of the tanks received the order to invade the Polytechnic; while doing so, it crushed those climbed on and standing behind the gate. Immediately afterwards, terror and chaos prevailed; thousands of people were trying to escape the police and the ESA (Greek Military Police) brutality, as well as the snipers’ gunfire coming from rooftops of buildings around the Polytechnic.

According to a study by the National Research Foundation, 24 people were killed in and around the Polytechnic. The total confirmed number of injured between 15 and 17 November was up to 1,103.

The end of the Junta

The events of the Polytechnic revealed how little popular base did the dictatorship have. And it opened the floodgates for people to openly question its authority. This in turn led to an internal crisis of the regime. Colonel Yannis Ioannidis, the hard-liner head of the Millitary Police, staged a counter-coup to block Papadopoulos’ attempt for a controlled “liberalisation” of the regime. However, the Junta’s final act came some months later, after the tragic events in Cyprus.

The regime attempted to harden its stance and proceeded to organise a coup on July 15, 1974, resulting in the overthrow of the President of the Republic of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios. This was the perfect excuse for the lurking Turkish army to invade Cyprus on July 20.

The students’ and workers’ heroism at the Athens Polytechnic uprising is a source of inspiration for young activists to this day. It represents a living proof that people, when they come out in struggle, can bring down even the most repressive regimes. Until today, November 17 is a day of remembrance and struggle. Mass demonstrations are organised in big cities, especially Athens which was the center of resistance. This way the struggles of the past and of today are linked, as the demand “Bread, education, freedom” is pending up to date.