by Elizabeth Stride

The gleaming surfaces of the five-star hotel’s bridal suite are sprinkled with loose powder, splotches of mascara and the odd dropped false lash. Pads are being squished into pantyhose and large feet into six-inch pumps. Outside, a cluster of hotel staff flank three Covid compliance officers, there to administer one final check of every performer’s health kit. Green means go. Orange or red, and 800 people are going directly into centralised quarantine.

This is Beijing in November 2022. The CBD is deathly quiet. The city is on the verge of yet another crippling lockdown. For weeks it has been assumed that the British Ball, a traditional and somewhat messy knees-up by the British Chamber of Commerce, will be cancelled, just like almost every other large-scale event in the city since early 2020.

But somehow the police raid doesn’t happen. Nobody is hauled off in trucks. The show goes on. And five drag queens, one English, one Swedish, one Canadian, one American and one Chinese, take to the stage as the Spice Girls.

And they bring the house down.

I’m proud to say that I stood among them. As Geri, naturally.

Modern Beijingers living in the shadow of Xi Jinping might look back at the city they inhabited during the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics and wonder what the hell happened. When I touched down at the shiny new Foster and Partners-designed international airport and hailed a ramshackle taxi in my then-broken Mandarin, I felt, like so many others who joined me in the international students’ dormitory in the Beijing Film Academy, that this was the place to be.

The opportunities seemed limitless. I joyfully compared the place to 1920s New York during broken Skype calls to my parents. On any given day I could find myself performing in an improv comedy show, yelling into a Bakelite telephone dressed as an LA gumshoe in some low-budget action flick, or participating in a poetry salon in a smoky bookshop.

Within weeks of arrival I was presenting an online TV show about same-sex marriage and surrogacy. I’d never found much joy in the gay bars and clubs of my native land. Here, there was only one club, so the city’s queers devoted their time to taking over any space that’d accept them. If the Thought Police were listening at every keyhole, nobody around me – including my Chinese activist friends – was afraid enough to stop.

Inevitably, I wound up in battered drag, performing a cappella hits from UK showbiz trio Fascinating Aïda to support a friend who was running a pop-up Weimar Germany-themed cabaret evening at a dive bar called the Hot Cat Club, in a warren of hip bars and hole-in-the-wall shawarma vendors in Fangjia Hutong in the heart of the old city that first Mao and then the Olympic city planners so nearly bulldozed.

For a brief period, queerness was able to flourish in the Chinese mainland. Rigorous but inconsistent State censorship was more concerned with policing chatter around the Three Ts (Tibet, Taiwan and Tiananmen) than locking up boys who wore makeup. An influx of contemporary pop culture thanks to the ready availability of illicit DVDs and, more importantly, the Internet, exposed a generation to androgynous K-pop idols, Thai kathoey performance artists, Brokeback Mountain and RuPaul’s Drag Race. Tens of thousands of affluent youth studied abroad, returning having experienced, among other things, a gradual mainstreaming of queer culture overseas, and, didn’t see there as being much of a problem.

As Time Out Beijing’s first and only dedicated queer columnist, I found plenty of material for a readership increasingly interested and involved in a blossoming gay culture from Guangzhou to Dalian. Queer underground churches. Tours by American and Japanese gay porn stars. Queer-oriented sex toy stores. The country’s only all-gay reality TV show, and a queer sitcom that followed (both of which aired on the fledgling online TV channels outstripping State television in the ratings).

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a prestigious but almost entirely cosmetic ‘advisory body’ of influential citizens ranging from athletes to billionaires, was even hearing proposals on legalising gay marriage. If LGBTQ equality was being mentioned in the lofty halls of politics – and, more importantly, being permitted to appear in State media coverage, surely the country was poised for change.

We’ll never know. The last public consultation on marriage equality closed in 2019 and the overwhelming response to it was hushed up by official censors. Even as Vietnam relaxed its official stance on LGBTQ+ individuals and Taiwan broke ground by being the first Asian country to usher in marriage equality (ironically for some commentators who wryly observed that, according to the CPC’s official view of the world, China had in fact legalised gay marriage in one of its provinces), LGBTQ+ equality has, in the era of Xi Jinping’s increasingly tight grip on authoritarian power, first waned and then gone into full retreat.

Tropes associating LGBT people with paedophilia, mental illness and the old classic ‘foreign forces’, that never fully vanished either among socially conservative Chinese or the legion of online ‘hard left’ commentators keen to promulgate a version of MAGA with Chinese characteristics, have returned to mainstream dialogue. Pride celebrations were shut down or stymied. Gay bars restricted advertising or were driven out of business by police harassment or interfering neighbours.

Finally, in 2023, the Beijing LGBT centre, a leading institution in the country that supported a generation of queer Chinese, from teenage runaways to parents of queer children, closed its doors for the last time, citing ‘forces beyond our control.’

I’d spent many happy hours at the Centre’s longest-serving location, a scrappy apartment in a nondescript development close to Beijing’s Liufang station. A tatty set of rainbow curtains, shelves lined with well-thumbed books, with queer theorists alongside tomes on law, culture and a good selection of romantic novels in multiple languages, and a tired digital projector made the tight space increasingly feel of another era. It harkened back to the pre-Communist days, when clandestine salons of intellectuals, revolutionaries and the demimonde of Peking gathered out of sight of either Republican police or, later, Japanese occupiers to plot a bright course for a fledgling nation casting off the ruins of Imperial mismanagement and colonial exploitation.

I loved it. It inspired me. For a decade or so there was a feeling of forward motion. But it was fleeting. In my last five years in Beijing, my dear queer Chinese friends began to drift away to seek opportunity, particularly to marry or to legally transition, overseas. This trend accelerated during Covid, when horrific and interminable lockdowns and a vast expansion of the State’s capacity to monitor your activity and who you kept company with – even your DNA – further eroded any sense of privacy or individual agency.

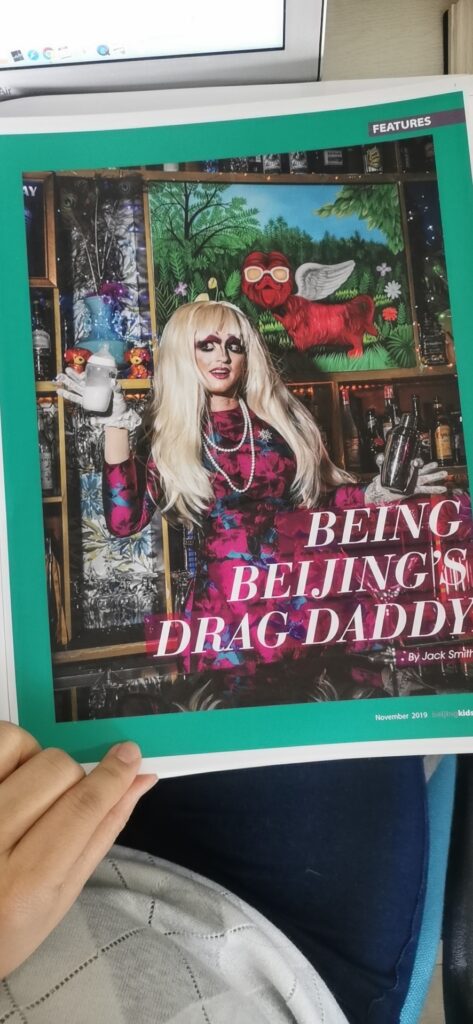

And yet, through it all, somehow, drag endured. Together with a number of Beijing-based amateur drag queens, I formed Haus of Lily, a response to the unfair working conditions weekend drag queens were expected to agree to. We syndicated, campaigning to earn the same amount gay bars were paying for DJs, gogo boys and other performers. We spent two to four hours in hair and makeup and our outfits could cost up to £150 a time, but managers and impresarios assumed we did it ‘for fun’, equating what we felt was performance art with some kind of psychosexual need.

While China has a storied tradition of female impersonation ranging from the superstar danjue roles in traditional opera to contemporary stars of stage and screen like singing legend Li Yugang, Western-style drag, epitomised by the polished, commercial queendom of RuPaul’s Drag Race, was new to China. Drag Race’s emerging underground popularity and the gradual transition of nightlife venues from discreet hookup spots to raucous entertainment venues, meant I was in the right place at the right time. We lost some gigs after unionising, but we took control of those we booked, and soon we were delivering high-quality themed night-long revues in increasingly upmarket venues.

Whether strutting our stuff as Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and Cher in a five-star hotel restaurant, dolling ourselves up in full Nashville regalia to host a Deep South-themed brunch complete with inflatable alligators, or throwing a Halloween party so epic that we had to hastily evacuate the venue when we got wind the police might arrive, for a brief time, it felt like drag could be a unifier, an element of queer culture that wasn’t anathema to the rising tide of State endorsed social conservatism, an art form that could, perhaps, maintain that fragile thawing of social attitudes towards queer people that had meant so much to so many in the post-Olympic years.

Since my departure, I’ve witnessed no loosening of the Chinese State’s attitude to queer liberation. Much like feminism, accessibility and internationalism, many guiding principles formerly vaunted by its leadership (if not honoured in practice or policy) have been abandoned.

For the first time in 20 years, there are no women among the 24 members of the Communist Party’s Politburo, or among the vice-premiers. Instead, the demure, elegant femininity of first lady Peng Liyuan is held up as the embodiment of feminine achievement – a military singer who famously abandoned a successful career to marry a bureaucrat who went on to preside with apparent absolute power over an 80 million-member Communist Party and the national government it permits to do its bidding. The implication is clear. The best thing a woman can do is marry and reproduce. Queer people don’t (can’t) do either, therefore there’s no space for them.

Western views of Chinese society are heavily influenced by Western media narratives shaped, in large part, by the very propaganda China’s State-controlled media and communications industries generate with the intention of presenting a strong, unified and ever-advancing party-state. It’s hard to blame those who view Chinese people’s beliefs as monolithic, its society homogenous and unimaginative, and its culture both vapid and exotic. If you tuned in to the annual Chinese New Year Gala aired by China Central Television (under its unironic acronym CCTV), that’s precisely what you’d experience. China’s government wants you to think of its people as a faceless, nameless mass of Party-loving patriots.

I know that’s not the case. Much has changed in the world since the heady days of 2008. But my beloved drag sisters – those who have remained in China – continue to perform in public. They continue to represent the far-from-revolutionary idea that individuals should be able to express themselves. And as long as that idea endures, drag will continue to be both a weapon against bigotry, and armour to protect some of the most vulnerable – and talented – performance artists on the planet. From Buddhist monks to cops, college students to minor officials, cleaning ladies to Embassy security guards, school children to senior citizens, the drag that Haus of Lily delivered only ever seemed to put smiles on Chinese faces. People everywhere seemed to appreciate drag for what it was – provocative, yes, but also relentlessly entertaining. The supposedly progressive West, the US with its drag bans and the UK with its politicisation of gender identity, could learn a thing or two