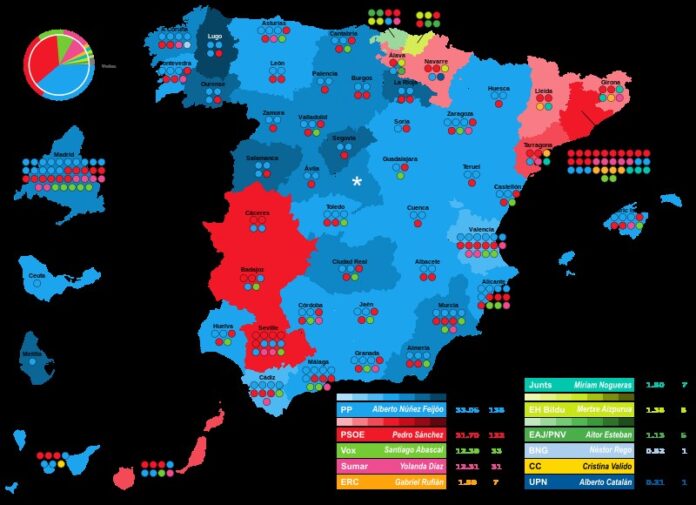

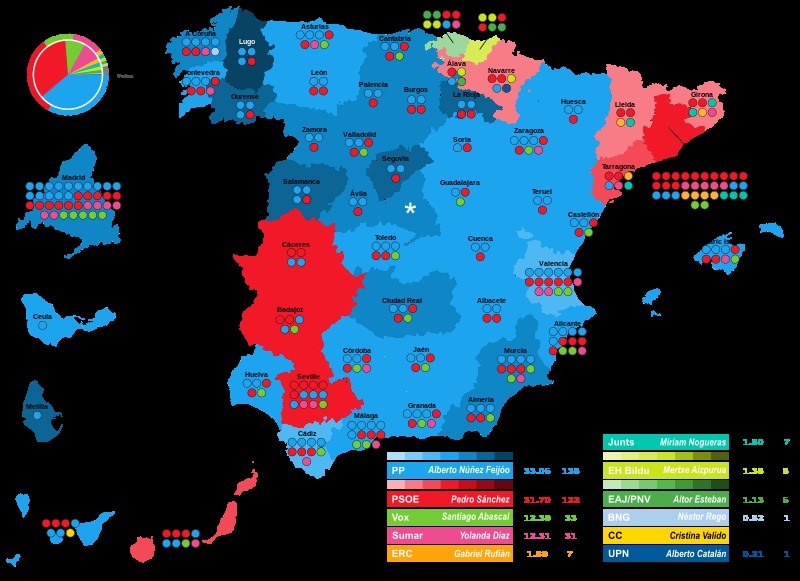

The snap elections in Spain last Sunday, 23 July, saw the right-wing bloc of PP (conservative) and Vox (far right) fall short of the majority that had been predicted by many polls and commentators. Despite PP coming first, with 33% of the votes, it is more likely that the centre-left coalition of PSOE (social democratic) and Sumar (neo-reformist left) will stay in government for another four years. It is also likely, though, that the polarisation expressed in these elections and the underlying problems driving it will exacerbate in the coming years.

The political polarisation witnessed in previous elections only intensified. This time, however, it found its expression, paradoxically, in the reinforcement of the mainstream parties of the neoliberal centre – PP and PSOE. That is largely due to tactical voting, of course, but also to the move away from the centre, in relative terms, of both parties. Over the past few years, PP in particular has radicalised its discourse, adopting a more free-marketeer stance, most prominently through the president of the Madrid region, Ayuso, and ultra-conservative positions on socio-cultural topics such as feminism. The latter illustrates the ongoing process of mainstreaming the far right, most obviously seen in the breakdown of the fabled cordon sannitaire, now a thing of the past: following the local and regional elections in May, PP and Vox are currently in ruling coalitions in over 140 local authorities. While the growth of PP in the Sunday elections meant a loss for Vox (which won around a third fewer seats now than in 2019), it also shows the complications in mass consciousness and the persistent influence of neoliberal and conservative ideas.

While PSOE hasn’t moved as much to the left as PP did to the right, it is clearly to the left of “the reformism without reforms” displayed by most of European social democracy, most recently by UK’s Labour Party return to neoliberal, pro-austerity positions. By contrast, the social measures of the PSOE-led government – although a far cry from the kind of policies needed to tackle Spain’s structural problems – have made a difference for the living standards of the popular classes. Most important among these measures were the rise in the minimum wage, the revaluation of pensions in line with inflation and the reform of the labour law to provide more protection to workers on casual contracts. Together with the fear of the far-right coming into government for the first time since Franco, it is these social concessions that allowed PSOE gain two extra seats and be now likely to remain in government. Thus, together with its counterpart in Portugal (Socialist Party), PSOE is one of the few remaining successful social democratic parties in Europe today, who are otherwise still trapped in the neoliberal paradigm they have been endorsing for the last few decades.

Of course, PSOE is ultimately a pro-capitalist party, as reflected for example in the allocation of the EU recovery funds that mostly benefits big business. Neither is the neo-reformist agenda of Sumar (a broad coalition of Podemos, Izquierda Unida, Mas País and other left groups, led by Deputy Prime Minister Yolanda Díaz) sufficient to address the country’s socio-economic problems – from low wages to housing to underfunded public services to the impact of climate change. Indeed, as noted here before the elections, some of its most ambitious proposals, such as the creation of a public bank and a public energy company (without taking the private companies in public ownership though), are likely to be watered down in a renewed government coalition with a strengthened PSOE. It is hard to see how and to what extent Sumar – which won a bit over 12% of the votes, slightly behind far-right Vox – will be able to push PSOE to the left in the coming years.

Tactical voting was perhaps most evident in the very poor results for the radical, anti-capitalist left: while Catalan, pro-independence party CUP lost both its parliamentary seats and over half of the votes it had received in 2019, the initiative Adelante Andalucía led by Anticapitalistas (formerly in Podemos) failed to meet the 2% threshold in the only province it stood candidates, Cádiz, and is also out of the parliament. This meagre performance will surely make the radical left across the Spanish state reflect on its orientation, strategy and tactics for the next period. A move away from the electoralist and institutionalist logic that guided these political forces in recent years and back to a grassroots approach of building new movements around the key issues facing the popular classes is the only way forward.

In Catalunya, PSC (PSOE’s Catalan organisation) consolidated its good score from the regional and local elections in May to become the region’s dominant political force. With Sumar and PP coming in second and third respectively, both of which are in favour of ‘Spanish unity’, the pro-independence parties gained less than 1 million votes combined for the first time since 2010. This signals that, following the upheavals of the past decade, independentism is likely to be a dead project for at least a generation, having lost its popular appeal from the peak of 2017. The independentist side, split across class lines, has failed to offer an inspiring vision of an independent Catalan republic. A more positive result came from Euskal Herria (Basque Country), where Vox gained less than 3% of the votes and the neo-reformist left party EH Bildu – with historical links to the former ETA that were incessantly used by the right-wing propaganda ahead of the elections – consolidated its electoral breakthrough. Bildu is now tied with PSOE and the centre-right nationalist PNV as the biggest party in the region.

It is the support (or, more likely, abstention) of these and other regionalist parties that a PSOE-Sumar coalition would need in order to stay in government. This means the national question is – despite the results in Catalunya – likely to remain at the forefront of politics in the Spanish state. Indeed, precisely because of the weight of the national question, the negotiations between PSOE-Sumar and regionalist parties – the Catalan ones in particular, eager now to prove their independentist credentials after the poor electoral results – might well fail and trigger a new round of elections.

These elections have seen a reinforcement of the political centre and the bipartisan system. It signals, therefore, the end of the cycle of social upheaval and mobilisation of the 2010s, which found its expression in mass developments such as the Indignados movement, the rise of Podemos or the Catalan struggle for independence. A new cycle has begun that will give rise to new movements and political projects, as the polycrisis of capitalism is deepening. In order to offer a way out, these movements and parties will need to have a more radical programmatic and strategic outlook – a task whose level of success will ultimately depend on the conscious and cohesive intervention of the revolutionary left.