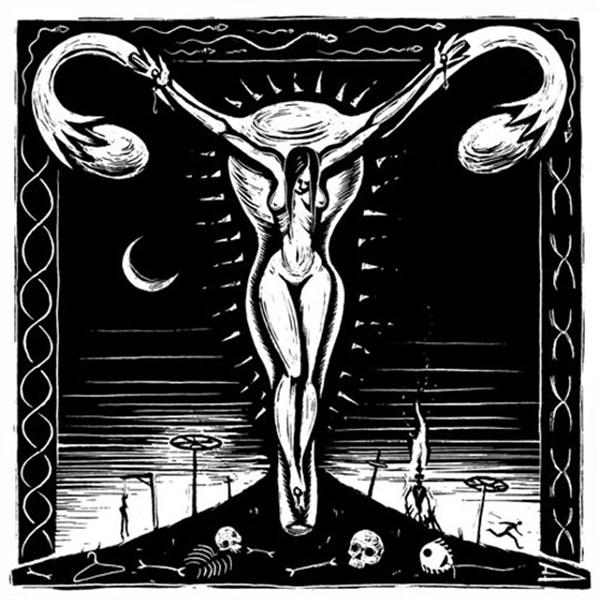

The oppression of women has not been an omnipresent feature of human society throughout all of human history. While women are certainly universally oppressed in today’s world, this has not always been the case, nor was it in all places throughout the course of history.

There are several anthropological theories about the exact origin of women’s oppression, but accurate information about the prehistoric times is still scarce. Research is ongoing, and new evidence comes to light often. These are dynamic sciences, so it is not possible to be very specific and certain about exactly how and when the oppression of women began.

From matriarchy to patriarchy

While we are sure that matriarchal societies were very common in prehistoric times, it is not correct to say that matriarchy was dominant in all pre-agrarian societies. It is well established that social relations changed after the first permanent settlement, when agriculture became the basis of the economy. This is the moment when patriarchy became the dominant trend, but we can’t be sure about the exact timeline. Matriarchy, on the other hand, did not vanish completely afterwards. We know that there are still matrilineal / matrilocal / matriarchal communities in some places in the world. However, it is not accurate to believe that all matriarchal societies were egalitarian. Power relations were also present in some matriarchal social constructions.

If we remove the sexist glasses we are usually wearing and study anthropological research with an open mind, we will find out a lot of information showing that the tasks usually attributed to women are not prestigious; we will also see that the role distribution between the sexes is often asymmetrical in many societies.

Along with all these methodological caveats, it goes without saying that human societies are shaped by relations of production and reproduction. As these relationships change, social transformations inevitably follow. The oppression of women, the transformation of the division of labour between the sexes into a sexist division of labour, the inferiority of some races to others, precede the formation of class society and prepared its material basis.

The key factors that created women’s inferior social position came with the transition from the hunter-gatherer economy to a higher system of production based on agriculture, livestock farming, and urban crafts. The primitive division of labour between the sexes was replaced by a more complex one. Higher productivity created a considerable surplus that first translated into internal differentiation and then into deepening divisions among the various layers of society. Women’s subversion did not “naturally” result from any biological difference. It was the result of revolutionary social changes that destroyed the egalitarian primitive communist societies, most of which were matriarchal, and replaced it with a patriarchal class society. The new patriarchal class model was marked by many forms of discrimination and inequality, including inequality between the sexes, from its initial stages.

Women’s oppression in Marxist classics

There is a widespread belief that Marx and Engels did not focus enough on the plight of women. However, this is not true. This impression is a result of a dogmatic reading of Marxism, as well as related practices that emerged with the degeneration of the Russian revolution in the 1930s.

Marx and Engels were among the first ones to believe and declare that the social situation of women is an important indicator when it comes to the evolution of societies. They argued that male dominance developed in certain historical conditions and humanity could not be truly emancipated until the oppression of women was ended.

Marx’s studies about societies include analyses of family and personal relations; including how relations between genders interacted with the relations of production. In The Holy Family, he qualified women’s situation in bourgeois society as inhumane. He even paraphrased the words of the French utopian socialist Charles Fourier eloquently:

“Change in a historical period is determined by the progress of women on the road to freedom. The emancipation of women is the natural measure of emancipation in general.”

While references like this were not mentioned in Grundrisse and remain very limited in Capital, Marx does not ignore the position of women or in what ways family, private property and the state operate and shape their position. He rather analyses the different elements of societies in their dialectical unity.

In his Ethnological Notebooks, Marx studied Morgan, as Engels also did later. In this book he deals with issues like the development of societies and the formation of classes and the state, in a holistic link with male-female relations and the family institution. In Notebooks, Marx makes the distinction and uses the concepts of production and reproduction of life.

Engels wrote Origins of Family, Private Property and the State, based on Morgan’s studies concerning egalitarian societies. These were ancient and prehistoric societies where no private property, state or systematic oppression of women existed, and where the family was not considered as a primary social institution. Engels attempted to complement Marx’s effort to interpret Morgan’s studies in terms of historical materialism. At the same time, we should take into account that Origins is limited to the scientific knowledge of the 19th century and was written on that basis. According to Engels, who followed Morgan on that issue, primitive communist societies based on simple agriculture were also based on kinship. However, as technology and productive forces developed, so did class societies. In this way, the gender-based division of labour was transformed into a gender oppressive division of labour, which led matrilineal societies to turn into patriarchal ones.

Engels’ work contributed very much in proving the historical forces behind the transformation of women’s social role and therefore concluding that women are not doomed to be oppressed to the end of time. In Origins, Engels clearly distinguishes the productive activity of people between production and reproduction. He defines reproduction as the production of people’s own labour power and the maintenance of the species. According to Engels, nationalising the means of production and abolishing the nuclear family as the basic economic entity of society, are key to achieving women’s emancipation.

Marx and Engels look at the interplay of productive forces and relations of production in order to define the mode of production of each period. The level of cooperation and power balances that hold people together, are determining factors of the mode of production. Relations of production, at the same time, exist in a much wider framework than the boundaries of production itself, and provide the overall status quo of society. They also create the ground for social conflicts.

This analysis rejects the singular determinism of technology and the economy. It also reveals that the mechanisms of oppression and control, such as sexism and racism, are power relations that ensure the continuity of the mode of production and a given kind of relations between classes.

From theory to the women’s movement

Clara Zetkin, one of the well-known figures of the German Social-Democrats, wrote in an 1896 article that capitalism, which is the modern mode of production, creates specific problems for women.

Zetkin distinguishes bourgeois women from proletarian women, and deals with the latter’s problems and demands. Zetkin distinguishes bourgeois women from proletarian women, and deals with the latter’s problems and demands. For her,

“as far as the proletarian woman is concerned, it is capitalism’s need to exploit and to search incessantly for a cheap labor force that has created the women’s question.”

She underlines that proletarian women have demands related to freedom but also economic ones. Therefore

“the liberation struggle of the proletarian woman cannot be similar to the struggle that the bourgeois woman wages against the male of her class. On the contrary, it must be a joint struggle with the male of her class against the entire class of capitalists”.

Held in 1907, the International Socialist Conference of Women Workers aimed at unifying the struggle of the socialist movement (in various countries) with the struggle for suffrage for women and establishing permanent relations between women’s organisations around the world. As we understand from Kollontai’s report, the inability of Social Democrats to defend the struggle of “universal suffrage without gender discrimination” in different countries was one of the main impulses behind women coming together to defend their rights. And if gender equality would not become an integral part of the proletarian class struggle, women should fight against gender discrimination within the ranks of workers organisations, too.

We know that Rosa Luxembourg, who was clearly a socialist feminist even though she is not well known in this respect, considered writing articles about women’s rights and demands as “a very urgent matter”, for which “every lost day is a fault!”, as she mentions in a letter to Clara Zetkin.

In her 1912 article “Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle”, she defends the suffrage of proletarian women who are already struggling against male privileges defended by the capitalist state. In the same work, she gives a clear answer to those who distinguish between productive and non-productive labour:

“As long as capitalism and the wage system rule, only that kind of work is considered productive which produces surplus value, which creates capitalist profit. From this point of view, the music-hall dancer whose legs sweep profit into her employer’s pocket is a productive worker, whereas all the toil of the proletarian women and mothers in the four walls of their homes is considered unproductive. This sounds brutal and insane, but corresponds exactly to the brutality and insanity of our present capitalist economy. And seeing this brutal reality clearly and sharply is the proletarian woman’s first task.”

Gender and class

Gender roles were historically formed earlier than class, and male dominance was a decisive and enduring historical force. This reality has led many feminists to argue that gender discrimination is the most appropriate lens to view the continuity and reproduction of oppression in any system.

But gender and class are intertwined, as is clear from Engels’ work in Origins and beyond. Class society and the sexist division of labour/patriarchy are two linked processes. Class is the center of Marxist politics for socialist feminists, but at the same time, gender or racial oppression cannot be reduced to economic exploitation. These aspects of our lives are inseparable and systematically linked; class is always gendered and racial.

In all cases, capitalism has endorsed patriarchy, as a system and as an ideology. Gender stereotypes have existed for thousands of years before capitalism, as we can see on scripts and findings from ancient civilisations. This is certainly related to the base/superstructure scheme that Marx describes. Yet, family structure and gender division are not static. These are systems connected with the evolution of society. They change as society changes. Here, we have proof for the dialectic relation between base and superstructure. Changing the relations of production can create the conditions for change in human relations. But these relations need to be specifically named and analysed.

Some socialist feminists view capitalism and sexism as separate though intersecting systems of equal importance. Just as capitalism is based on relations of oppression and on the workers’ exploitation by capitalists, patriarchy is a system in which men dominate women. This is known as the “dual system” view.

Marxists on the other hand don’t reduce the importance of women and LGBTQI+ oppression to the class issue. They don’t consider gender oppression as of minor importance. Instead they identify the root of the race, sex and any other oppressions to class relations.

We can see that sexism under capitalism has taken a whole new form and has become a very useful tool for the system and one of its key components. Sexism cannot be eradicated as long as capitalism is still in place. Yet, sexism, racism and other forms of discrimination will not magically disappear on the day one after the revolution. Changing mentalities is a long process that will not materialise just by decree and legislation. Changing people’s minds is a process based on both education and material actions. Through these improvements i.e. the application of Marxist theory, it will soon become clear that life in a socialist society is far superior to capitalist society.