Fifty years ago, the British government was actively considering the forced movement of one third of the population of Northern Ireland in a desperate attempt to stabilise a situation which was spiralling into ever deepening chaos and violence. An all-out civil war seemed possible, even likely.

Today these events are only half-remembered. This is convenient for political forces which thrive on sectarian division and who push forward with dangerous agendas. The workers movement -the trade unions and left activists and groups who are seeking to win both Protestant and Catholic workers and young people to the ideas of socialism- have a duty to remember the events of the “Troubles” and to draw the correct political conclusions.

‘Ruthless force’

On 13 July 1972, following the breakdown of a temporary Provisional IRA ceasefire, the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath ordered the drawing up of contingency plans in case the breakdown became “irrevocable”. Heath feared a scenario where “the security situation in Northern Ireland had deteriorated so far that the government were on the point of losing control of events”.

The plans included a “direct military assault upon extremist-dominated Roman Catholic areas of the Province with the aim of securing a total victory over the IRA coupled with a neutral, if not acquiescent, attitude towards the activities of the UDA [a paramilitary group in the Protestant community]”. The disarming of the Protestant population through the withdrawal of licensed guns was also considered, however.

Under the plan, 300,000 Catholics would be moved west of the River Bann and 200,000 Protestants in the opposite direction (in total one third of the population). If necessary, force would be used against those who refused to move. Forced population movements would be preceded by two earlier measures. On “P-Day” a State of Emergency would be declared and on “R-Day” the number of British army battalions on the streets would be increased from 20 to 47 (bringing troop levels to 50,000). The official who drew up the plans admitted that he was “extremely doubtful” of successful implementation as “great resistance” would result, and the government would have to be “completely ruthless in the use of force”.

On the edge of civil war

The British government were forced to consider such measures because by 1972 the North was on the edge of civil war. Nearly 500 people died in that year and over 5,000 were injured. These numbers have to be understood in the correct context. The population of the North is small, and it was only 1.5 million in 1972. Bloodletting on this scale in England, Scotland and Wales would have resulted in 20,000 deaths and 200,000 injured, and for the USA 70,000 dead and 700,000 injured.

The state had mobilised large numbers of armed men but was struggling to contain the situation despite the adoption of “anti-insurgency” methods borrowed from a series of wars in Britain’s colonies over the previous 25 years. In total, the state had 32,000 police and troops at its disposal. The Royal Ulster Constabulary, an armed and militarised police force had grown from 3,000 in peacetime to over 6,000. 23,000 regular British soldiers had been deployed and were supplemented by 6,000 members of the newly formed and locally recruited Ulster Defence Regiment.

The strength of the paramilitary and vigilante organisations which sprang up in the early 1970s is difficult to gauge as they operated in the shadows. In the Protestant community the Ulster Defence Association was capable of putting 40,000 on to the streets. The Ulster Volunteer Force was smaller, but still numbered several thousand. There were half a dozen smaller armed groups, such as the Red Hand Commando and the Orange Volunteers. The Ulster Special Constabulary Association (USCA), formed by ex-members of the recently disbanded police auxiliary force (the “B-Specials”) claimed to have 10,000 members and had declared its willingness to mobilise in the event of a major escalation of violence.

In the Catholic community, the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA both grew quickly after internment without trial was introduced in August 1971, and especially after Bloody Sunday when 14 unarmed demonstrators were shot dead by British troops in January 1972. The Officials were the largest group initially, with 10,000 youth in their periphery, but were overtaken by the Provisionals in time. On paper the largest group in the Catholic areas was the Catholic Ex-Servicemen’s Association (comprised of former members of the British Army) which claimed numbers between 8,000 and 20,000. It was mostly unarmed and engaged in the defence of Catholic areas through the manning of barricades, but like the USCA had declared its intent to arm and fight if a civil war developed.

If we accept a conservative estimate of 50,000 members of the various paramilitary and vigilante organisations in 1972 and compare this to the larger population of England, Scotland and Wales (Great Britain or GB) this would equate to 2.5 million, mostly young men from working-class communities, on the streets. The corresponding figure for the USA would have been 7 million.

Workers Move to Check Sectarianism

The British government was responsible for brutal repression, mostly directed against the Catholic community. By the end of 1972, the British army had shot 150 dead, including in a series of mass casualty events (for example, 11 died in the “Ballymurphy massacre”, 5 in the “Springhill massacre” and 6 in the “New Lodge Road massacre”, all in Belfast). Nearly 2,000 had been interned without charge or trial (equivalent to 80,000 in GB or 270,000 in the USA).

Over 100 British soldiers died in 1972. The Official IRA called a ceasefire in May of the year (in part after a movement against them of working-class people in Derry after they killed a local British soldier home on leave) but the Provisionals were only in the early stages of a campaign which was to last for 25 years. The paramilitary groups, including the Provisional, engaged in what became known as “tit-for-tat” sectarian killings in which hundreds died in a cycle of retaliation and counterretaliation.

The situation seemed hopeless. But it was not repression or stalemate between competing paramilitary groupings which prevented violence escalating to the point of all-out civil war. It was the power of the organised working class. The trade unions organised a quarter of a million workers, and importantly, this was the era when rank and file shop stewards in the factories and workplaces were prepared to act independently of the union bureaucracies. They also thought politically, many under the influence of the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) or the Communist Party. In the 1970 general election 100,000 had voted for the NILP despite the unravelling political situation.

When rioting and shooting first erupted on a widespread scale in August 1969, it was the influence of class-conscious working-class activists which prevented the violence spreading even further. A mass meeting of 8,000 shipyard workers voted to protect all workers from attacks from sectarian forces. This event was mirrored by countless examples in other workplaces, and in working-class streets and estates. Activists grouped together across the sectarian divide and prevented the expulsion of workers from their homes and workplaces, at least for a period.

At the time, the small group of Marxists organised around the Militant newspaper argued that the workers movement should go further and form an armed trade union defence force. From the distance of half a century, this call can be dismissed as abstract and meaningless but in the turmoil of the time, it had meaning. In fact, even the upper echelons of the trade union bureaucracy discussed the possibility.

The trade union leaders did not act and ceded the initiative to sectarian politicians and the paramilitaries. During 1972, 1973 and 1974, the workers movement was less visible and in retreat. Nevertheless, it continued to hold the line in the workplaces and on a local level. There are many examples when workers took action to counter sectarian killings. For example, on one occasion in 1974, the mixed workforce at a meat processing factory called Abbey Meats on the outskirts of Belfast, walked out in protest after a machine gun attack on a car carrying workers into the plant, which killed two.

Kingsmill Massacre

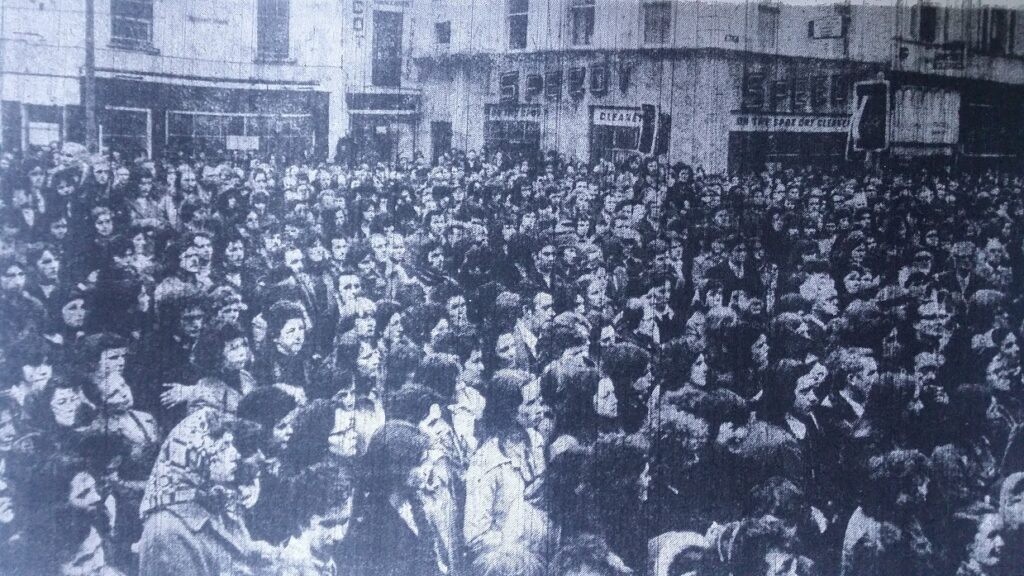

In late 1975 and early 1976 the sectarian bloodletting reached a crescendo. In December 1975 the IRA shot dead two Protestants in the centre of Derry. The Trades Council (a structure which brings together trade union branches and activists in a town or district) called a protest and 5,000 came out. In January the carnage continued. Six Catholics belonging to two families (three Reavey brothers and three O’Dowd brothers) were murdered in their South Armagh homes on the night of January 4th by the UVF in collusion with members of the state forces. The next day, a Provisional IRA unit stopped a minibus containing 12 workers returning home from a clothing factory. They lined them up beside the bus, told the one Catholic to walk away without looking back, and mercilessly machine-gunned the 11 Protestants. Ten died whilst one miraculously escaped with 18 separate bullet wounds and lived to tell the tale of what became known as the “Kingsmill massacre”.

In the following days, the Trades Councils in Newry and the Lurgan-Portadown-Craigavon area called strikes and protests against the killings and thousands responded. These three regional strikes and demonstrations were the first generalised response from the workers movement for several years. In the weeks and months that followed the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, under pressure from the rank and file, organised the “Better Life for All Campaign”. The Campaign did not develop the dynamism and confidence that was necessary despite the efforts of Militant supporters who argued that it should take up the class issues of poverty and unemployment which were feeding the violence, robustly oppose sectarianism, and take up the issue of state repression. The weakness of the response of the official movement meant that later in 1976, the Peace People, in effect a cross-class alliance, provided an outlet for the intense yearning for peace in working-class areas. Hundreds of thousands joined demonstrations over the course of several months.

The protest movements acted to check the paramilitaries and the number of sectarian killings fell sharply from 1977 onwards. In May 1977, hard-line unionist politicians attempted to organise a general strike (of Protestants) with the support of paramilitary muscle. Trade unionists defied the organisers and faced down intimidation and threats. In desperation the paramilitaries shot a Protestant bus driver dead when he continued to work, but it was too late: the organised working class had defeated a reactionary Loyalist stoppage. Militant supporters and other lefts played an important role in mobilising workers through a campaign organised by the Labour and Trade Union Co-ordinating Committee.

Workers will always find a path of struggle, even after long periods of quiescence. When they do, actions on one front will often result in advances on another. The mobilisations against sectarian attacks in December 1975 and January 1976, and the movement which broke the Loyalist stoppage in 1977, gave confidence to the trade union movement and meant that from 1978 Northern Ireland workers were at the forefront of the wave of strikes which peaked in the ‘Winter of Discontent’. In the early years of “Thatcherism”, the most advanced workers turned to the political plane and in the 1981 local elections trade union activists stood under various banners including as Derry Labour Party, and Antrim Labour League.

The movement had gone from anti-sectarian actions in defence of workers lives, to the industrial movement for better pay and conditions, to the political arena, in a few short years. At every stage the role of class-conscious shop-stewards and the small numbers of Marxist activists was to provide leadership, often at great personal risk.

Lessons for Today

The threat of politically motivated violence has not gone away and the idea that it can always be contained by the state is false. If in the early 1970s violence escalated close to the point of civil war, it could happen again. The past will predict the future without the conscious intervention of class-conscious workers and left activists.

The trade unions were the bulwark which prevented an all-out escalation in the 1970s, 80s and 90s and continue to counter sectarian threats and attacks today. The trade unions remain united and by European standards are strong in membership and organisation but there are forces which are working to undermine this unity. The unity of the unions must be consciously defended from those who seek to divide us.

If the political arena continues to be dominated by sectarian parties, society will move inexorably towards increased division and ultimately renewed conflict. We need a mass political party which represents the interests of all workers from both a Protestant and Catholic background and those who have come to Northern Ireland from other places.

Mass movements will provide the fertile ground on which a new mass party will be built. The current wave of industrial action has brought tens of thousands of workers into conflict with their employers. Many realise that the sectarian parties do not represent their class interests and some are drawing the necessary conclusions. If even small numbers of workers scan the horizon in search of an alternative left, activists have a duty to provide answers and to demonstrate in practice what is possible. There are some on the left who have turned towards nationalism and reject the idea of a mass, anti-sectarian left party. There are others who accept the need for such a party in words but who hesitate and vacillate. We cannot afford to wait. We have a duty to start the hard work required to build an alternative. Class-conscious workers and anti-sectarian left activists must rise to the challenge and act now in unity, with an immediate focus on bringing together a slate of candidates with an agreed basic socialist programme for the local elections in May.